Nov 10, 2023

When Communities Oppose Large Solar and Wind Installations

Of all the elements needed for a successful siting of a large-scale solar or wind installation, a key one is trust. Essential to trust is transparency — from the earliest planning efforts to the final approvals.

By: Joel Stronberg

We — and by we, I mean all of us in the United States — have the reliable price-competitive technologies needed to transition the nation to a low-carbon economy. Although new and improved technologies will come along, we have what we need in terms of alternatives to fossil fuel-generated electricity.

To achieve the president’s greenhouse gas emission reductions with solar and wind requires a lot of land. Acreage estimates vary between models depending upon the assumptions used to run the programs.

With a 13% to 14% solar panel efficiency, National Renewable Energy Laboratory researchers estimate that 22,000 square miles of solar panels would be needed — roughly the size of Lake Michigan.1 At 20% efficiency, a conversion rate thought possible by solar experts, land use drops to 10,000 square miles — roughly the size of Lake Erie.2

It’s estimated that between 1,400 and 10,100 miles of new high-voltage lines will be needed annually to achieve net zero power-sector emissions in 2035,3 reaching “1.3 times to 2.9 times current capacity.” The wide range in estimates reflects how much is not yet known about where the new generating facilities will be sited and where the end users are.4

Not everyone is thrilled to have a utility-scale wind or solar installation next door. Even those who favor the use of solar, wind, and other clean energy alternatives have a different view of things when a large-scale project is planned for just down the road in an otherwise rural or scenic setting.

I’ve written before that pushback on renewable energy projects can take different forms,5 including legal challenges and political campaigns.

A 2021 Ohio law (S.B. 52) allows county governments to create exclusion zones where no utility-scale solar or wind projects can be sited.

At least 11 counties in Ohio have availed themselves of the law.6 An effort by Apex Clean Energy to override the denial of its plan to construct a 300-megawatt project in Crawford County, Ohio ended up on the November 2022 ballot. The ban was upheld by voters, while the debate leading up to the election was fraught with “alternative facts.”

A recent study by the Columbia Law School documents state and local opposition to renewable energy projects.7 In its most recent iteration, it identified 59 new local renewables-siting restrictions across 35 states. The total number of restrictions is now 228 and appears to be rising.

The “restrictions include temporary moratoria on wind or solar energy development; outright bans on wind or solar energy development; regulations that are so restrictive that they can act as de facto bans on wind or solar energy development; and zoning amendments that are designed to block a specific proposed project.”

It doesn’t help any that U.S. climate policy is a hostage of the U.S. culture wars in which party affiliation tends to dominate all other issues. But it’s a mistake to think that antagonism is just a Republican thing.

Opposition to large-scale projects is an area where climate change believers and deniers have found common ground. There are various reasons why communities reject proposed projects. Politics certainly plays a part, but so too does how some project developers have presented their proposals as fait accompli rather than as the start of project-planning processes with community involvement.

A study published online in the journal Rural Sociology8 surveyed residents in western and northern New York about their views on utility-scale solar farms.9 It found that only 44% of those surveyed supported an installation, 42% opposed a project, and 14% neither opposed nor supported it.

It’s the conclusion of the authors that the strongest reason for opposing the project was that the communities didn’t know what they’d be getting out of it.

“What’s in it for me?” is a valid question for which there are answers. Why not give the community a discount on utility rates? Or calculate how a utility-scale solar installation and farming are totally compatible? Why not explain how important the transition to a low-carbon economy is to the future of the nation’s health and security?

It now appears that residents in Staunton, Virginia will have an opportunity to enroll in a program of Dominion Energy10 that comes with an estimated 10% reduction on the company’s bills just for subscribing. The offer is part of a deal that the utility is trying to make for a large solar project. The offer of a sweetener comes after opposition to the project rose up to meet the developers.

It is not at all clear, however, that there will be a project in Staunton. The experience of the Virginia community is fairly representative of the problems — many of which are self-inflicted — facing developers elsewhere.

The project developer for the Staunton project was not particularly secretive about its application for a 97-acre site to be rezoned for the proposed 15.5-MW solar energy installation. Notices of various zoning and planning commissions were publicized in various places. It appeared the project was working its way through the application processes according to established procedures.

There’s a big difference between not being particularly secretive, i.e., following the rules, and making the community actually aware of what was being done. Experience dictates that developers of utility-scale solar and wind projects need to be deliberate about bringing communities in early in the planning process.

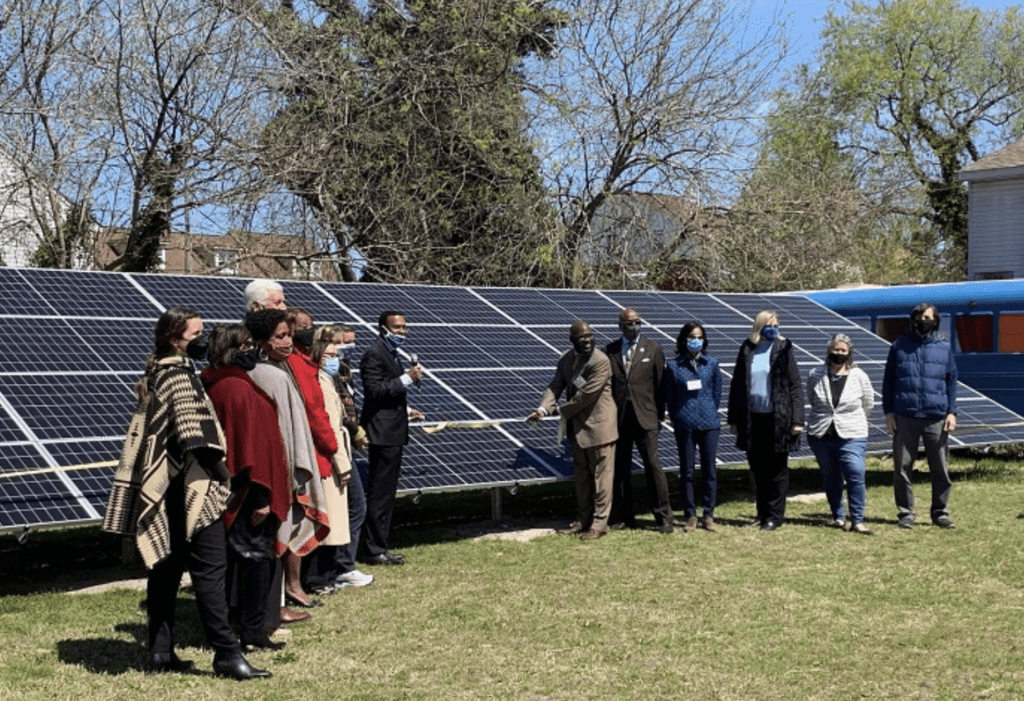

In 2017, Georgetown University inked an agreement with MD Solar 1, a subsidiary of Origis Energy, to construct a 100,000-panel, 32-MW solar project on a 537-acre tract in Charles County, Maryland about 30 miles outside the District of Columbia.11 The project was part of the university’s overall commitment to reduce its carbon footprint in part by shifting to electricity generated from solar and other clean energy resources. The proposed project would have supplied over half of the university’s electricity demand.

To make a long story short, the university abandoned the proposed project and decided to buy clean energy credits from existing solar installations. It didn’t have to be that way. Among the issues that could have been resolved were things like sightlines. A buffer zone of trees or earth berms could have been sited that would have essentially hidden the installation from casual view.

There are multiple ways to hide solar installations using berms and plantings. In the case of Georgetown University, making up for the lost panels could have been done by using the rooftops of university buildings or partnering with the many big-box stores in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area. Also, cooperative arrangements could have been made with the D.C. government and the Biden administration to use the rooftops of government buildings.

A timely willingness by the developer to modify plans in response to concerns can go a long way — although it’s no guarantee of approval. In Staunton, the developer has now shown a willingness to work through issues.

Beyond offering Dominion Energy customers the sweetener, the developer is reported to be working to resolve a list of community concerns. The planning commission has recommended approval of the project, but only if a list of 20 conditions are met, including installation of fencing and landscaping measures and limitation of glint and glare from the solar panels.

The Staunton project may be an example of too little, too late. Based on media reports, the developer’s failure to be proactive in reaching out to the community from the very beginning is still being held against it.

Of all the elements needed for a successful siting of a large-scale solar or wind installation, a key one is trust. Essential to trust is transparency — from the earliest planning efforts to the final approvals.

A final note on the Staunton project concerns the unwillingness of opponents to accept the final decisions of the planning, zoning and other commissions; boards; and governing units. Opponents of the project have made it clear that they are still exploring all avenues to either slow down or stop the project from happening. One can’t help but to think that everything would have been a whole lot easier if the developer took the time to do it right from the start.12

Not every problem has an amicable solution. And often the opposition is deeper than NIMBYism (Not In My Backyard). The failed Cape Wind project planned for Nantucket Sound was challenged by the Wampanoag tribe because it would have infringed on important cultural traditions around an unobstructed view of the sunrise in the region.13

The Cape Wind project failed, but it’s not as though all proposed wind projects off the Massachusetts coast have been rejected. Offshore wind projects like the 800-MW Vineyard Wind have been approved. Vineyard Wind is 15 miles south of where Cape Wind would have been built, and thus further out to sea.

As Greg Alvarez wrote in Forbes, “opposition [to projects] may not be organic.”14 Communities slated for proposed solar and wind installations are becoming ground zero in the battle between the fossil fuel industry and clean energy interests.

Local battles over large solar and wind installations are being funded in some cases by fossil fuel interests, who flood the communities with specious studies and misinformation. In Ohio, the group Citizens for Clear Skies claimed that wind turbine noise was causing birth defects in Portuguese horses.15 Then, too, there are the claims by former President Donald Trump that wind turbines cause cancer.

The Texas Public Policy Foundation, an ultra-right think tank, is a leader in the movement against the use of environmental, social and governance criteria in the investment decisions of states, companies and individuals.16

The foundation has released a YouTube video17 that, according to National Public Radio, “features multiple falsehoods,18 including the untrue statement that the proposed project didn’t do any environmental impact assessments19 and the incorrect idea that offshore wind projects ‘haven’t worked anywhere in the world.’”20

A good discussion on where opposition funds are flowing from is the Volts podcast “The right-wing groups behind renewable energy misinformation.”21

It’s difficult to follow the money from some of the citizen organizations back to fossil fuel interests. Groups like Alliance for Wise Energy Decisions and Citizens for Clear Skies crop up where projects are being proposed and maintain the aura of “a group of neighbors getting together.”22, 23

These citizen groups either cease existing once their work is done, i.e., a project is killed, or continue to maintain the same neighborly character. Project advocates that encounter these types of groups should do their due diligence work, e.g., search records and ask questions of the groups directly, to discover whether the groups are what they say or are part of a network of opposing fossil-fueled organizations.

It’s vital to remember that even avid environmentalists who otherwise support the transition to a low-carbon economy may oppose a particular project. Siting large facilities is an issue that crosses aisles. It’s personal.

At times, local environmental/conservation groups may end up at odds with their nationals. The Ivanpah Solar Power Facility project proved to be a major battleground between the Sierra Club’s national office and its local chapter. In the end, the national quashed local chapters’ opposition to some solar projects with a 42-page directive — with mixed results.24 The local San Bernardino chapter changed its name and went on opposing the project.

The massive amount of land and offshore acreage needed to make the transition a reality is a problem that the physical sciences can’t solve. Large scale solar- and wind-project developers need to understand that project siting and construction is much like politics in that it’s local. Developers and activists need to engage with the community even before the first permit application.

Sources

- https://tinyurl.com/n7e693fn

- https://tinyurl.com/7wt8j2a5

- https://tinyurl.com/ycxe5jae

- https://tinyurl.com/452zn9j4

- “Depoliticize to Decarbonize,” an article to be published in the Fall 2023 issue of The Environmental Forum.

- https://tinyurl.com/4bhtb9w9

- https://tinyurl.com/4s5zp7fr

- https://tinyurl.com/2p9emttk

- https://tinyurl.com/4b54bfjn

- https://tinyurl.com/mr22mznr

- https://tinyurl.com/4ruabm69

- https://tinyurl.com/mr22mznr

- https://tinyurl.com/2p9xxfpj

- https://tinyurl.com/bde9f3pd

- https://tinyurl.com/369f9anb

- https://tinyurl.com/y5euze3n

- https://tinyurl.com/2n9zkvmp

- https://tinyurl.com/ysaz359y

- https://tinyurl.com/2u4xf8at

- https://tinyurl.com/ysaz359y

- https://tinyurl.com/5bwn2wwu

- https://wiseenergy.org/

- https://tinyurl.com/2dcjr5su

- https://tinyurl.com/yc7yyymc

This article originally appeared in Solar Today magazine and is republished with permission.