Aug 30, 2024

Heat, Health, Racial Injustice, and Affordable Housing

Affordable housing is falling short of protecting its residents from the health impacts of a rapidly intensifying climate. Hotter indoor temperatures and building materials that off-gas toxic chemicals are combining into another form of climate-induced racial injustice.

By: Gabby Davis

According to a new study from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, around 18 million rental units in the United States are vulnerable to climate change and extreme weather events. Further, a 2020 study based in California found a disproportionate number of low-income Californians living in subsidized housing in hotter neighborhoods. People of color with lower household incomes are more likely to live in hotter areas compared to whiter neighborhoods. Research shows that both Black residents and residents with lower incomes often live in neighborhoods up to seven degrees hotter than in suburban areas only a few zip codes away.

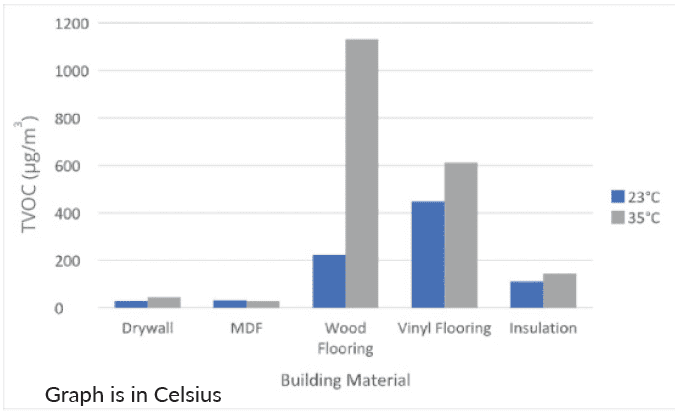

Affordable housing often has building products that can pose health risks to its occupants including vinyl flooring, SPF insulation, sealants, and adhesives. New research being developed is producing evidence that hotter temperatures result in higher incidences of chemical exposure inside the home. Because of this, retrofitted and new affordable housing should be built with healthier, third-party certified building materials to lessen the heat-amplified exposure of hazardous chemicals that are detrimental to human health.

The Issue

Rapidly intensifying climate and hotter temperatures are concocting a pressing environmental concern for indoor air quality. A few studies have looked at the effects of rising temperature in correlation with altering the chemical landscape of the indoor environment. There is emerging evidence that heat will make commonly used building products such as engineered wood flooring degrade and increase exposure to volatile organic compounds (VOCs). VOCs are harmful because they can cause eye, nose, and throat irritation, headaches, loss of coordination and nausea, damage to the liver, kidney, and central nervous system. Some VOCs can also cause cancer.

Researchers found that, “The VOC emission rate can increase significantly under increased temperature, thus global warming and heat waves in summer may lead to higher indoor VOC source emissions in the years to come.” Building products found to have increased VOC emissions when exposed to continuous high heat include:

- Gypsum drywall panel;

- Medium-density fiberboard (MDF) panel;

- Engineered wood flooring;

- Vinyl flooring; and

- Batted fiberglass insulation.

New (but limited) research is showing that heat increases the amount of exposure to harmful chemicals from suboptimal building products often found in older, lower-income neighborhoods. Think about the concept of thermal degradation: materials exposed to higher heat for a longer duration will wear substantially faster than those exposed to more moderate temperatures and exposure times.

What Does All This Mean?

High heat will worsen indoor air quality. Building products can contain toxic chemicals that lead to a higher concentration of airborne pollutants and worsen indoor air quality (IAQ) when released into the air.

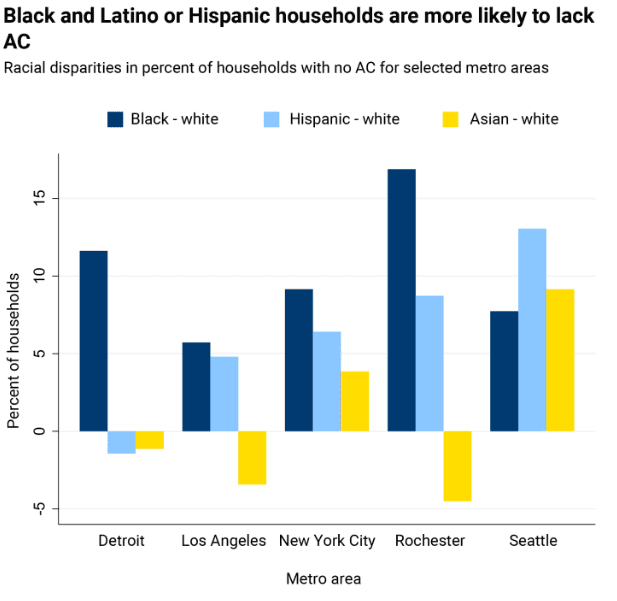

People of color are most at risk of experiencing subpar air quality. Previously redlined areas, which are predominantly inhabited by people of color (32% Black and 30% Hispanic), can face up to 8 degrees Fahrenheit hotter temperatures than non-redlined areas. This is due to the lack of natural heat protection found in many of these areas. Formerly redlined areas tend to have older housing stock and command lower rents. These less-valuable assets contribute to the racial wealth gap. Redlining curbed the economic development of minority neighborhoods, miring many of these areas in poverty due to a lack of access to loans for business development.

People of color have less convenient ways to keep their homes and themselves cool. About one in ten homes in the U.S. do not have access to air conditioning. Many of those homes belong to Black or Latino families.

Solutions

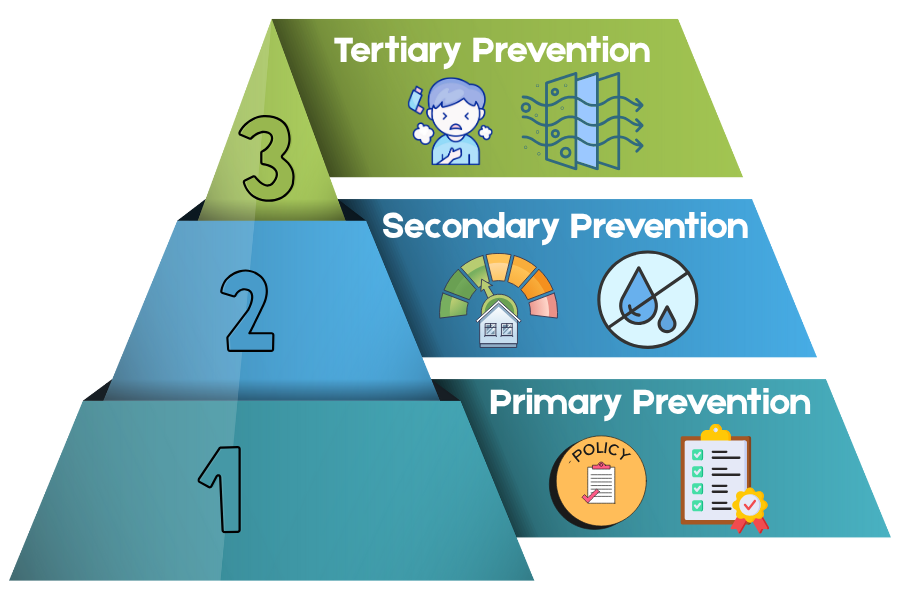

1. Building and Retrofitting Affordable Housing with Healthier Building Materials

Policymakers should develop policies that incentivize or subsidize green building certifications. Developers should incorporate green building certifications into their properties. This includes material health, renewable energy generation, and climate resilience measures—for example, the Living Building Challenge, LEED, or Enterprise Green Communities.

Retrofits and new construction should employ product selection that minimizes harmful chemicals by choosing building products—especially interior finishes—with health certifications.

Healthier Product Alternatives

Lessen exposure to hazardous chemicals by building with certified products.

- Best: Products certifications and labels that are free of the most hazardous chemicals include Cradle to Cradle, Cradle to Cradle Material Health Certification, Living Product Challenge, and Red List Free.

- Better: Product certifications and labels that limit some of the worst chemicals include GS-11 (Green Seal); Living Building Challenge Red-List Approved.

- Good: Product certifications and labels that limit VOC emissions include low- or no- VOC products with the following certifications: GREENGUARD Gold, Indoor Advantage Gold, FloorScore, Green Label Plus. Install ERV or HRV ventilation systems ideally with MERV 13 filters or higher, to maintain healthier indoor air quality.

2. Be Efficient

Improve thermal efficiency, air sealing, and efficiency of appliances in existing buildings. For every $1 invested in weatherization, $1.72 is generated in energy benefits and $2.78 is generated in non-energy benefits, which include improved health, safety, and comfort.

Geothermal heat pumps are resilient to extreme heat events as they rely on consistent underground temperatures rather than air temperatures. In extreme heat, they would provide more effective cooling using less energy than air-source systems.

3. Integrate Innovative, Sustainable, and Efficient Design Strategies

Protecting existing flora and green spaces alongside planting trees will contribute to cooler localized temperatures for residents, as greenspace lowers temperatures and correlates with lower heat-attributable deaths.

Green roofs have been proven to help reduce heat islands by reducing roof temps from as much as 30-40 degrees Fahrenheit and ambient city temperatures by 5 degrees Fahrenheit. They can also reduce a building’s energy consumption and stormwater retention.

Incorporate emergency cooling strategies in case of power outage, such as including designated “cool rooms” with efficient cooling systems and refrigeration powered by solar panels, batteries, or a generator.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line is this: Rising temperatures are taking a toll on everyone. As a contractor, you have the power to mitigate the effects of climate change. By choosing less toxic and more energy-efficient building products and improving ventilation, you can create healthier and more comfortable homes.