Jul 1, 2025

An Ounce of Prevention: Building Performance Professionals as Public Health Practitioners

Building professionals are public health heroes, protecting communities through smart design and prevention.

By: Lindsay Fraser and Amanda Jimcosky

Benjamin Franklin is credited with being a founding father of the United States of America, but he is also a founding father of public health, laying out the most basic tenant of the field: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” He wrote this phrase in a 1735 letter to the editor Philadelphia society to create and implement fire prevention and protection plans, modeled after the Boston Mutual Fire Societies. Franklin cautioned residents to prevent residential fires, that could quickly burn down whole cities in the 1730s, by being mindful when moving hot coals around their homes, lest they unwittingly drop one on the stairs and start a fire (as Franklin himself had done). He also urged the citizenry at large to form “bucket brigades” of trained and organized individuals equipped with tools, like large leather buckets to carry water, to fight any fires that did occur.

Furthermore, he called for professional standards for chimney sweeps to strengthen the systems of prevention. By 1736, he had co-founded the Union Fire Company, the first in Pennsylvania, which has since grown into the Philadelphia Fire Company.

He and his fellow Union Fire Company members went on to form Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss of Fire, which has endured as the The Philadelphia Contributionship, the longest tenured insurance company in the country. Also of note in his letter was a prescription for improvement in building standards regarding roof safety: “I could wish, that either Tiles would come in use for a Covering to Buildings; or else that those who build, would make their Roofs more safe to walk upon, by carrying the Wall above the Eves, in the Manner of the new Buildings in London.”

Per the American Public Health Association, the goal of our public health system is to “promote and protect the health of all people and their communities. This science-based, evidence-backed field strives to give everyone a safe place to live, learn, work and play.” The foundation of the public health field in the USA is also the history of building safety and performance.

Levels of Prevention

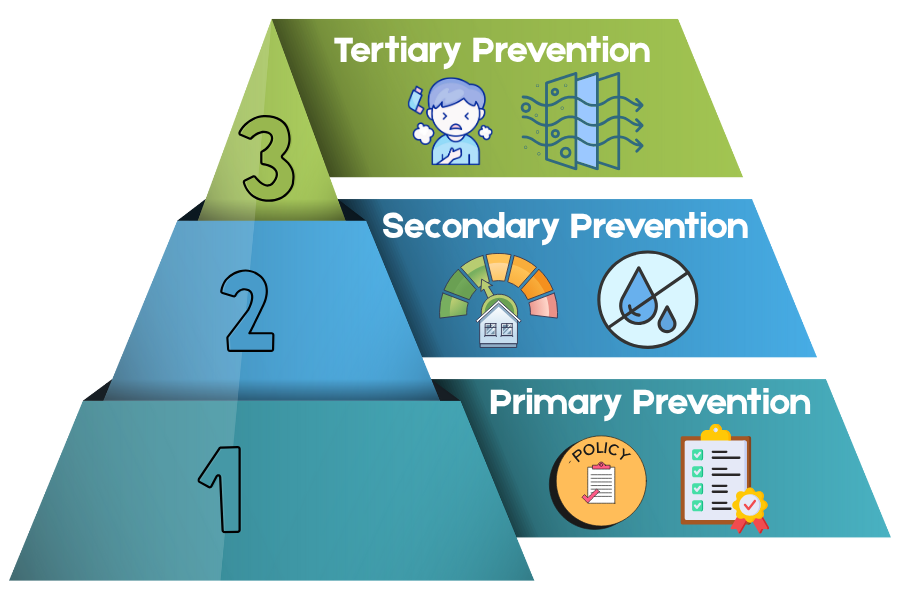

If a central tenant of public health is that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” it is worthwhile to explore the different levels of prevention and where the work of maintaining and improving our built environment sits along that spectrum.

A pleasant summer day swimming in a local creek can be a useful analogy to understand the three tiers of prevention (primary, secondary, and tertiary) and scope of work of the public health system: Imagine you and a friend are swimming in a creek and you see someone struggling as they are being swept downstream. You and your friend pull them out of the water, get them to safety, and then continue with your afternoon. Soon enough, someone else floats by in the same predicament, and then someone else, and then one more person. At some point, you and your friend look at each other and decide to investigate upstream to find out what’s going on. You find that there is a hiking trail that leads to a cliff and people are falling into the water and being swept downstream by the current.

Primary Prevention

Naturally, the next logical move is to put things in place to prevent this from happening. Signs along the trail would help, but that requires people to read them and choose a different path. A better option would be to re-route the trail so that it doesn’t go near the cliff’s edge. Preventing people from falling off of the cliff in the first place is called primary prevention.

Adding warning signs for people to read may be helpful, but system-level engineered solutions to protect health, like re-routing the path so falling isn’t even an option, are generally the goal. Often, this is achieved through policy. Policy can be governmental legislation, written into standard operating procedures, or design standards. Interventions that work on this level can be referred to as health promotion if they are also promoting well-being and not just preventing harm.

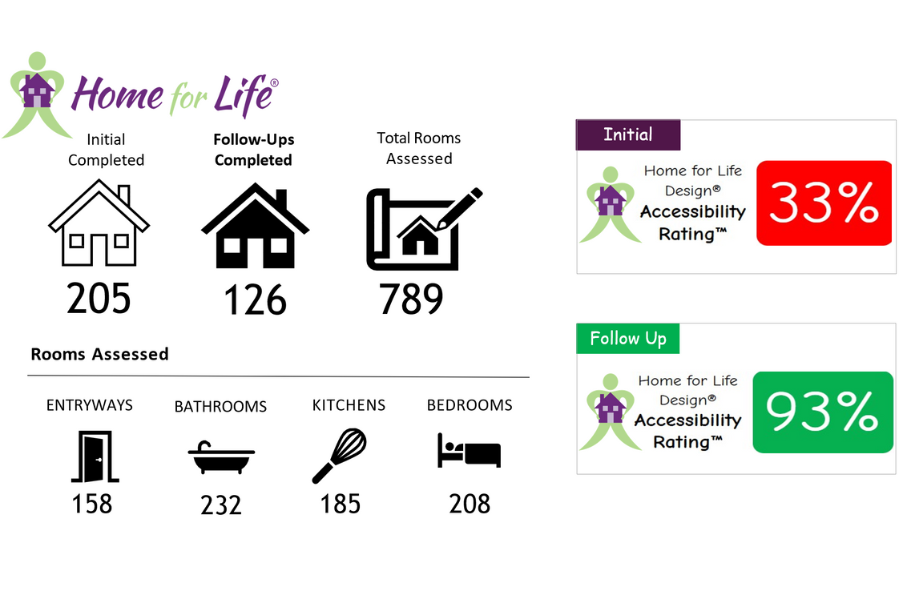

Primary prevention activities can be electrical codes that prevent fires or choosing green building materials with low VOCs and no lead. Rental inspections that test residences for lead hazards and ensures their removal before a child moves in is primary prevention. Designing buildings with considerations for air quality like high-filtration HVAC systems that can help prevent asthma and allergy attacks is primary prevention.

Secondary Prevention

We know that some people won’t read the signs or follow the path and may still fall off that cliff. Adding a net to catch people at or after the fall but before they get swept downstream is considered secondary prevention. Finding children with elevated blood lead levels (EBLL) through screening is secondary prevention, as is conducting a lead risk assessment to identify lead hazards in a home following an EBLL result.

Energy and water use restrictions during a heat wave could be considered secondary prevention. Blower door tests that identify inefficiencies that can impact human health are secondary prevention. Designing an efficient space that has low energy use, a tight envelope, healthy building materials, and an adequate HVAC filter system are further “upstream” activities.

Tertiary Prevention

There are people who fall through the cracks and end up in the water. Helping them to stay afloat and pulling them to safety is considered tertiary prevention. Interventions that take place at this level are often also considered harm reduction. This might look like cancer support groups, opiate addiction treatment, or physical therapy for a chronic pain following an injury. Lead abatement programs that remove lead hazards from home of kids with lead poisoning is tertiary prevention, as are home renovation programs that improve poor air quality and housing conditions for families of kids with asthma.

These are important and necessary programs and interventions to be sure. However, the goal of the public health system generally is to move services, programs, resources, and focus upstream as much as possible. It’s much better to prevent a pandemic than trying to keep an active one from getting worse, but interventions along the spectrum of prevention are critical to human health and progress. No matter which part of the “stream” we’re swimming in, building safety and performance professionals have been at the foundation of our public health system from the beginning.