Mar 6, 2024

Meet April Ambrose, The First But Not The Last

April Ambrose was born in the Ozark Mountains in a log cabin built by her parents. In college, she designed her own Environmental Education major. She started and grew nonprofits. She helped an organization grow from 2 employees to 130. Now she is trying to fix the workforce development pipeline into energy efficiency careers.

By: Macie Melendez

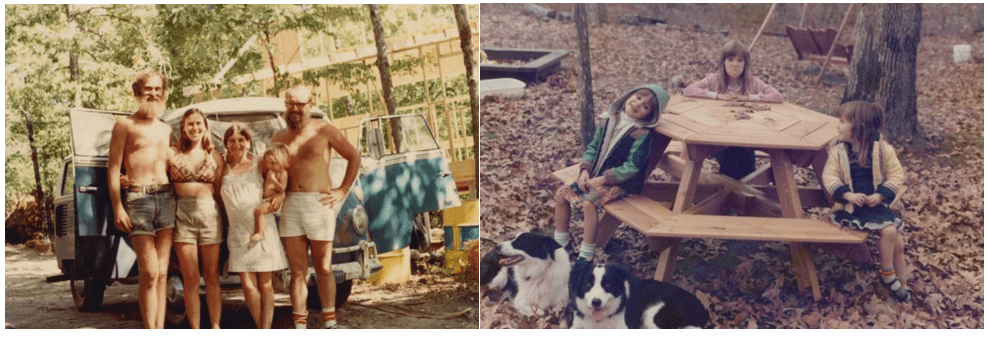

Born in the Ozark Mountains in a log cabin built by her parents, April Ambrose was raised in a tight-knit and highly educated community of hippies from the “back-to-the-land” movement of the 1960s. It was in her childhood where she developed an intrinsic understanding of sustainability.

After traveling around the country selling oak furniture at craft shows and festivals, Ambrose’s father became a Certified Nutritionist and opened a health food store. It was in her adolescence that she began to understand the juxtaposition of health and the environment, which would eventually form her career path.

By the time she was attending Hendrix College in Arkansas, it was clear to Ambrose that sustainability and education needed to be intertwined. So, she took it upon herself to design her own major. In 4 years, she graduated with a degree in Environmental Education (the first of its kind and one that helped shape the environmental science one offered at Hendrix today) and had completed the college’s first sustainability assessment. “It was at Hendrix that I developed my lifelong passions for sustainability, education, and mentorship,” says Ambrose.

After college, there weren’t many sustainability-related jobs to be had, so she chose to work for a local doctor. During those years, she also set up two nonprofits. One that helped patients with financial limitations to receive care and one that produced an annual event to showcase the link between health and the environment.

That work was recognized in 2005 by the National Environmental Trust (now the PEW Charitable Trust’s Environment group), who she then worked for on climate change policy and advocacy. “We set up over 15 events around the state to educate nearly 1,000 local and state leaders on the effects of climate change in Arkansas before my grant-funded position ended,” explains Ambrose.

In 2007, Ambrose became the first employee of Entegrity, a sustainable building consulting firm headquartered in Little Rock. In her 15 years there, Ambrose helped grow the company from 2 people in 1 office to 130 employees in 9 offices. Her roles included office manager, marketing, human resources, sustainability operations director, sales manager, and business development executive for sustainability and energy services.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

“For a long time, I was the only female at Entegrity, and very often the only female in most meetings that I was having,” says Ambrose. “I really never thought that much about the women that would come behind me and how we should grow the company to be equitable. I just kept plugging ahead: After I was good at project management, I moved into sales, and then after I got good at sales and started looking for my next thing, I got into building performance visualization tools for a while. And then I got into diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

Ambrose started a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion group within Entegrity and one of their first goals was to increase diversity among their staff. “So, this group had been operational for about a year, and COVID was going on, and we were getting some of our folks poached by coast companies, paying them coast prices while they continued to live in Arkansas. We just couldn’t compete financially,” she explains. “We realized it was unlikely that we would pull anybody from the coast to Arkansas, and that’s when we decided we had to home-grow a more diverse talent base.”

So, they shifted their thinking. Instead of looking at people with the skills to do the job, Ambrose and the group decided they’d hire without the skills and train them internally. This route became a training ground—growing candidates from a certain starting point and getting them into the industry.

In this process, Ambrose started thinking about the green jobs pipeline. While working with Lauren Waldrip of the Arkansas Advanced Energy Association—a local, member-based trade organization—Ambrose learned that workforce concerns were the main bottleneck to the industry’s continued growth. “So, we asked, ‘What does the green jobs pipeline look like in Arkansas? And where should Entegrity and other companies insert ourselves to enhance that so that we can benefit from it?’ It turned out there was no contiguous pipeline.”

As these conversations were going on, Waldrip started advocating on behalf of the industry to the Office of Skills Development (OSD) and applied for a grant of $2 million, over 4 years, to address this issue. “When she got the grant, she came to me and said, ‘April, I’m the dog that caught the car. I don’t know how to manage this…would you consider coming over to manage this work?’”

At the time, Ambrose was ready to take on her next challenge. Though it was difficult to leave Entegrity after 15 years, she said yes and started working with the Arkansas Advanced Energy Foundation in January of 2023.

Learning The Workforce Development Side

“I knew the industry I’d be serving very well, but I needed to learn the workforce side of things,” says Ambrose. Now, as the Director of Workforce Development for more than a year, she’s began to see some common roadblocks within the industry.

“One of the things I’ve seen a lot is companies that don’t know what they’re asking for,” she says. “Some don’t have job descriptions written down and some can’t define the skills they need. When I ask them about the absolute minimum, they have a hard time answering.” Ambrose says the industry is doing itself a disservice to not ask for candidates by skillset. “College is not the only indicator of success. If companies can post skills, it opens a wider candidate base.”

Additionally, Ambrose believes apprenticeships are a great way to define a clear path into energy efficiency. “The pathway here should be clear and should be evolving,” she says. “We have a burden in the industry to keep these jobs equitable by really defining the skills necessary to do the work. We owe it to our previous selves in how we found these jobs to develop a better pathway. And we owe it to the next generation to make that more clear.”

Ambrose also learned that a lot of companies look for employees thinking about the organization’s needs, but not about the person they’re hiring’s growth within the organization. “I try to show career progressions to employers. I didn’t realize how behind the industry was,” says Ambrose. “I think it’s because we all came into the industry at such different, weird angles, it’s hard for anyone to think about a clear, logical path from entry level to management.”

Professional Goals

Ambrose has several big goals she hopes to accomplish this year, among which are more local partnerships. “I want to create local partnerships between employers and training institutions that make a real difference,” she says.

Local partnerships help with training people locally—even if you’re using a national curriculum. Because a lot of organizations cannot train in-house, these partnerships are key to bringing in a diverse group of people into the energy efficiency industry.

“In traditional workforce pipelines, most folks aren’t exposed to these careers, and therefore don’t even know they exist,” she says. “So how can they aspire to any of it?” Ambrose also says the industry needs to do more than just tell students and younger people that these jobs exist. She says we need to go one step further and expose them to these jobs and the green energy pipeline. “I don’t want to tell people there’s work and then send them home to Google it,” she says. “I want them to know the jobs exist, how they can get there, and how much they pay. We can’t expect that everyone has the same connections, but we can expect that exposure to careers is impactful. There needs to be a connection there.”

A Discussion on Women

Often as the only woman in the room during her career, Ambrose found herself adjusting to “fitting in” with her male counterparts. “My advice to other women in the industry now would be to look back and see what you can do to ease the way for other women,” says Ambrose. “When I look back at my career, I realize I just meld easily. I became ‘one of the guys,’ made the jokes that would make them laugh. But then I can also look back and see just how important my mentors were to my evolution.”

Ambrose believes that women bring creativity, common sense, organization, wholistic thinking, future-proofing, and support of the whole person to the table. And she thoroughly believes that we need to throw “imposter syndrome” out the window. “If men can steamroll imposter syndrome, then we can too!” she says. “You can sit at the table, but it doesn’t do any good if you’re scared to speak. We need to change how we think about ourselves in the workplace.”

During her childhood, she used to play an educational game with her dad where he’d ask her math questions. With a pile of change in front of them, the money would go to her if she got the answer right and it would go to her dad if she got the answer wrong. “I didn’t see myself in a career in energy or math because I struggled in those ways. Watching the change all go to my dad told me that I wasn’t good at math, so I started telling myself that math just isn’t my thing,” Ambrose explains. “But just because it’s hard doesn’t mean it can’t be your thing.”

Now in the world of grants, Ambrose wishes she had more self confidence at a younger age so that she could learn those skills that were hard. “As women, we buy into these ideas of what women and men are good at and we don’t think we could be the anomaly. It’s easy to write off.”

Ambrose is taking her advice, though, and has taken steps to see how she can help others follow her path into the industry. “For me, this comes in the form of mentorships, public speaking, and creating things like Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion groups within my organization,” she says.

Ambrose may have been the first Environmental Education major at Hendrix College, the first employee at Entegrity, the first person to create several nonprofits to help people integrate energy and education, the first person to bring diversity, equity, and inclusion to her organization… but it certainly does not mean she’s the last. Her major is now available to others at Hendrix, there’s many more employees at Entegrity, her nonprofits still help others, and she’s opened the door for a diverse range of employees to get jobs in the industry.

“I made it to this point in my career,” she says. “Now I can help other people get here, too.”