Nov 17, 2023

Moving Toward Equity, One House at a Time

HUD Healthy Homes Program helps Alaska native villages adapt to change.

By: Molly Rettig

Chris Gene flipped a switch inside his old family home in Gakona, Alaska, filling the entryway with bright light.

“All this lighting can run off this switch here,” the electrician said, explaining the three-way system he had just installed.

“That’s good, you can see the whole room now,” Gene said. “My grandkids always wonder how come I have no lights.”

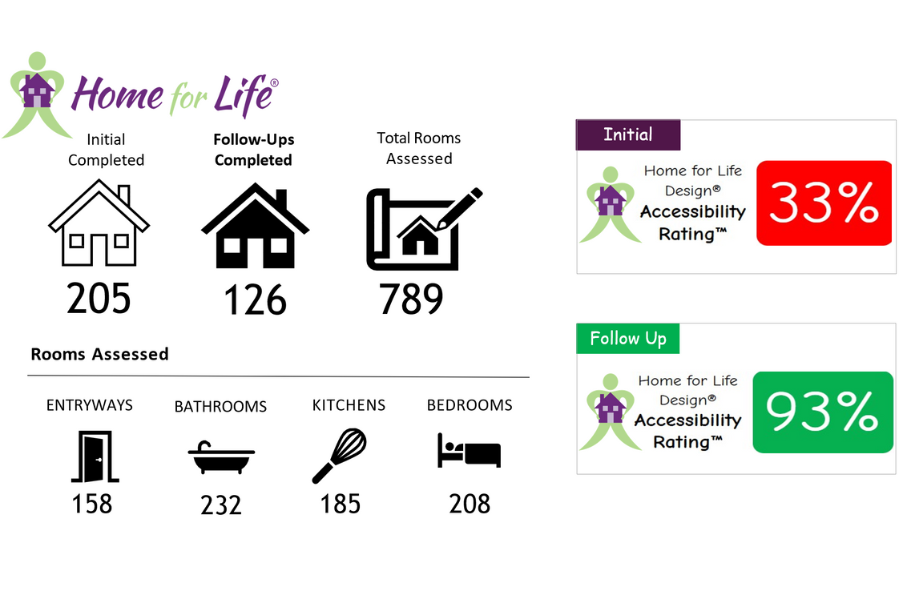

Gene is one of seven homeowners in Gakona getting health, safety, and energy-efficiency improvements through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD’s) Healthy Homes program, designed to reduce environmental hazards in underserved communities. The U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)—from its Alaska Campus in Fairbanks, previously the Cold Climate Housing Research Center—has worked with seven other Alaska communities on similar Healthy Homes projects—everywhere from the Arctic community of Buckland to the Yukon village of Galena to the small village of Gakona along the Tok Cutoff Highway in southern Alaska.

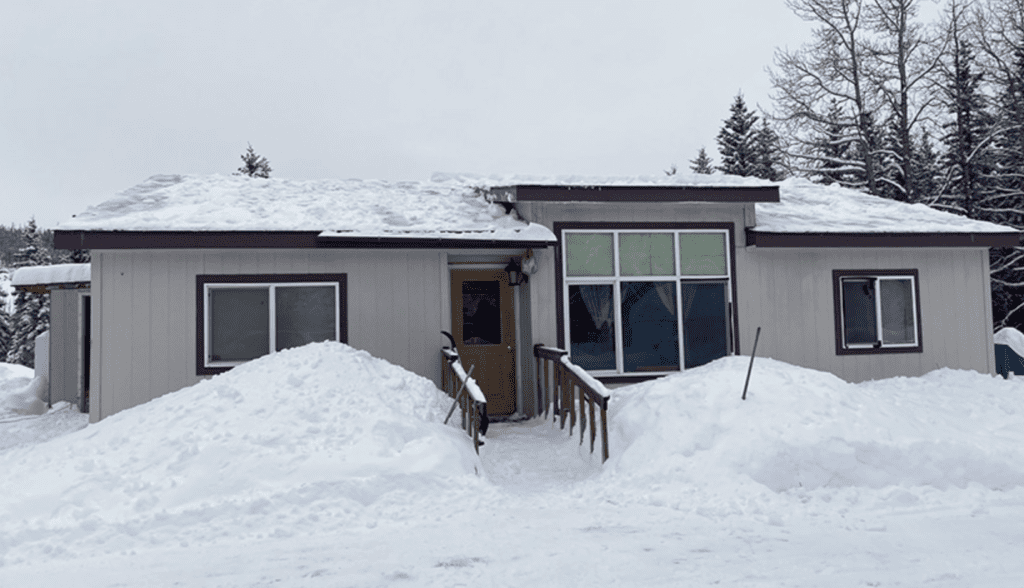

The Native Village of Gakona sits in a wide valley boxed in by mountains. To the north, the Alaska Range curves across the sky; to the south, the Chugach Range walls off the coast; and to the east, the 16,000-foot peaks of Blackburn and Sanford tower on the horizon. Weaving through these giants, the Copper River holds one of the world’s richest runs of wild red salmon. This region has been home to the Ahtna Athabascan people for thousands of years. While they used to travel in small groups from place to place, today they have mostly settled in eight villages scattered between the mountains.

“I’m an Udzisyu-Caribou clan, the biggest clan around here,” Gene said.

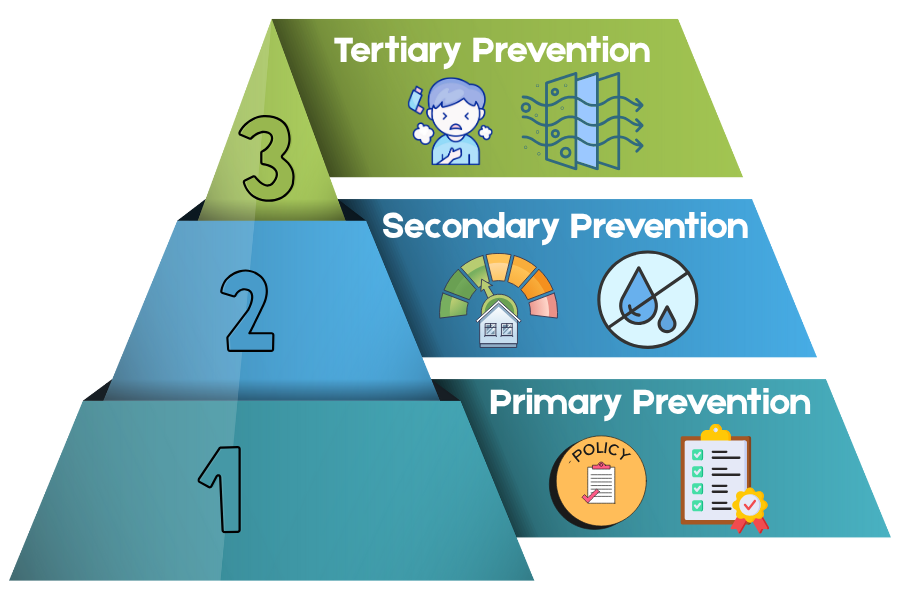

Despite their rich culture and knowledge of the land, Alaska Native communities face enormous challenges when it comes to energy, housing, and health. More than 3,000 households in rural Alaska still lack running water and wastewater, and Alaska Native elders and children suffer from the highest rates of upper respiratory distress in the United States, thanks in part to poor housing. While Alaska Native people traditionally lived in seasonal shelters built from log and other local materials, in the late 20th century they moved into homes provided by the federal government. These homes, however, were largely prefabricated outside of Alaska and were not designed for the extreme environment or frozen ground.

For example, Gene’s house sits on unstable soils in a low point in the valley.

“Every spring, water comes down and goes right underneath this house,” he said. “Kills off all the mice and stuff, but it makes my house tilt.”

It is even harder because Gene is paraplegic and uses a wheelchair to get around.

“I have to put my brakes on every time I get water, make coffee, otherwise I’ll roll all the way down here,” he said, letting his wheelchair coast down the floor.

Through the Healthy Homes program, workers upgraded lighting and ventilation in Gene’s home and also installed a handicap-accessible ramp so he could come and go safely.

While many NREL researchers are doing groundbreaking R&D to chart the nation’s path to clean energy, the Alaska Campus focuses on deploying these technologies in frontline communities. Sometimes that means creating new housing designs like a demonstration house in Unalakleet, working with ARPA-E and tribal partners to manufacture local, sustainable building materials, or helping entire villages like Newtok relocate due to coastal erosion.

While new technologies play a key role in the clean energy transition, it is also critical to improve what is already there, said Vanessa Stevens, a scientist at NREL’s Alaska Campus who is overseeing the Gakona Healthy Homes project.

“In Alaska, there is a lot of substandard housing, so retrofits will always be part of the solution,” Stevens said. “Our team tries to make sure the buildings at the bottom end of performance also receive attention, research, and remediation.”

Many rural Alaskans do not have the financial resources or knowledge to address the housing deficiencies they inherited. When new homes were introduced, with modern building materials and mechanical systems, most Native families received no training on how to operate or maintain them.

“It takes a lot of skill, learning how to maintain a home. A lot of people didn’t really realize that,” said Derrick Sinyon, environmental coordinator for the Native Village of Gakona, NREL’s partner on the project.

Sinyon has had to learn many of these skills himself at the home he shares with his wife and 3-year-old daughter. The double-wide trailer was manufactured outside Alaska and was not designed for 40-below temperatures or heavy snow loads. Over time, this has led to moisture problems in the roof and drains that freeze every winter, preventing them from using the shower.

He has structural problems, too, as climate change warms the permafrost. While typical homes on permafrost are elevated, the homes in Gakona sit directly on the ground. This allows heat from the building to leak into the ground and disrupt the thermal regime of the soil, which can thaw permafrost and set off a cascade of other problems.

Last winter, Sinyon noticed that the air coming through the heating vents was not as hot as it should be. When he went down to the crawl space to check the furnace, it turned out one of the ducts had fallen off and was blowing hot air into the crawl space. This heat loss had likely been going on for weeks, not only wasting costly energy but warming up space under the house that was supposed to stay cold.

“It got hot enough down there that my house shifted and left a crack in my ceiling. It even cracked my window,” Sinyon said.

Through the HUD Healthy Homes program, Sinyon was able to upgrade lighting, add vents to the roof to prevent mold growth, install heat trace on his water lines to prevent freezing, and make other retrofits.

Down the road, Roselyn Neeley is having even bigger foundation problems at the three-bedroom house she lives in with her husband and three children. As the ground underneath the house has thawed and settled, her foundation walls have sunk and slumped inward, creating a bow in the middle and throwing everything out of level.

“The settling is pretty constant. It can be all quiet, then suddenly you hear it start settling again. It sounds like something is rolling down the ceiling,” Neeley said.

In July, as part of the Healthy Homes work, a crew releveled Neeley’s house. In the crawl space, they found wooden beams that had rotted and concrete footers that had been smashed by the moving ground. They jacked up the foundation and installed steel beams under the house to stiffen the foundation. Neeley is hopeful the improvements will help her house, but she still worries about the health of her family living there.

While fixing homes in Gakona and other Healthy Homes communities makes an immediate difference for the families living in them, it has research value as well. The techniques being used to stabilize foundations, improve air quality, and reduce energy use will inform the next generation of technologies that will be deployed in rural communities and extreme environments nationwide.

NREL has worked with eight rural villages across Alaska on HUD Healthy Homes projects to improve the health, safety, and energy efficiency of homes in extreme climates. See a full list of Healthy Homes projects. And learn more about NREL’s Alaska Campus.

This article was originally published in the NREL News and is republished with permission.