Nov 1, 2024

The Importance of Including Non-Energy Benefits in WAP and Home Improvement Projects

Focusing solely on energy savings can overlook the broader benefits of energy efficient home improvements—here's why it's important to capture all of it.

By: Archana Ghodeswar and Bill Eckman

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is investigating methods to incorporate the non-energy impacts (NEI) of weatherization into cost-effective calculations.

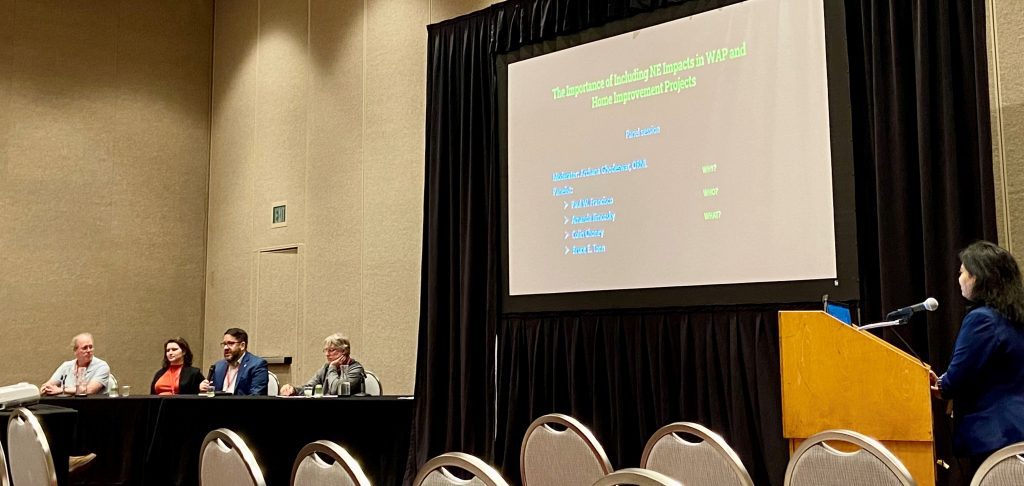

Researchers from ORNL conducted a panel session titled “The Importance of Including NE Benefits in WAP and Home Improvement Projects” at the Building Performance Association 2024 National Home Performance Conference & Trade Show in Minnesota. The panel session featured oral discussions with the panelists, who also submitted presentations.

Archana Ghodeswar, a Research and Development Associate at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, moderated the panel session, which aimed to explore several key questions surrounding the integration of NEI from experts who have contributed to weatherization and home improvement programs:

- Why should we include NE benefits in weatherization programs and other home improvement projects?

- Who should be involved?

- What are the potential metrics for quantification?

Introductions to the Panelists

Panelists for this session included Paul Francisco, Amanda Jimcosky, Colin Choney, and Bruce Tonn.

Dr. Paul Francisco is the Director of the Indoor Climate Research & Training Division and weatherization training center at the Champaign County Regional Planning Commission. He is also a Senior Research Associate at Colorado State University’s Energy Institute. He has been performing housing research for over 30 years with a focus on energy efficiency and indoor air quality. Paul is a certified BPI Building Analyst, Energy Auditor, Quality Control Inspector, and Healthy Home Evaluator. He was also the chair of the Building Performance Association board of directors.

Amanda Jimcosky is the Program Manager for Women for a Healthy Environment’s- Healthy Homes Asthma Program, which provides home renovations to low-income families in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. The program focuses on repair elements that increase the health and safety of the home, especially as it relates to asthma and allergies. By centering public health, she hopes to develop a system for revitalizing housing stock in southwestern Pennsylvania that adequately considers the health of both occupants and workers, the needs of a residential construction workforce, and its long-term outcomes.

Colin Choney is the Housing Rehabilitation Director at Green & Healthy Homes Initiative where he leads, energy efficiency, lead paint hazard remediation, and health and safety housing intervention services. He has more than 11 years of industry experience and, among his other contributions, he has served on the board of directors for the National Association for State Community Services Programs (NASCSP) and Maryland Building Performance Association (MDBPA).

Dr. Bruce Tonn is President of 3Cubed, which is a non-profit research organization located in Knoxville, Tennessee. Bruce secured a grant from the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) to build a system to alert elders about hazardous indoor environmental conditions. Additionally, Bruce has led projects to assess the health benefits of weatherizing low-income homes and contributed a lot to the single family and multifamily non-energy impact studies.

Defining Non-Energy Impacts (NEI)

At the beginning of the session, all of the panelists were asked about the definition of non-energy impacts. In their responses, they all mentioned health, safety, and comfort level as important aspects of the non-energy impact of Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) and home improvement projects. “One specific example could be that a project decreases the number of allergens and asthma triggers in a home, leading to decreased symptoms for an asthmatic child, leading to fewer medical visits and lower absenteeism from school,” said Amanda.

Now, we’ll answer the proposed questions we introduced earlier.

Why Should We Include Non-Energy Benefits in Weatherization and Other Home Improvement Projects?

“We know that there are many impacts from home performance beyond energy. Energy is just the ones that is easiest to quantify. People need to have homes be what they are intended to be—places that support their overall well-being. This well-being includes physical and mental health, the ability to go to school and work, and overall safety. When done properly and thoughtfully, there is little potential downside to home performance, but generally we only get to take credit for one piece: energy. It is likely that, for many households, energy is a small portion of the overall benefit. We should be able to value the other aspects,” said Paul.

Amanda asked the group to explore the rationale behind the non-energy impacts. “WAP and home improvement projects funded by public money fill gaps that many residents in underserved communities cannot address. The average age of a home in America is 40 years, with those in the northeast averaging closer to 60 to 70 years old. Many of these older homes have not been maintained or upgraded to withstand climate change that we are seeing now. Using a public health approach to center climate resiliency in WAP and home improvement projects can help identify environmental, health, economic, and social impacts to lessen the detrimental side effects of publicly-funded programs and ensure funds are being used most efficiently for the most positive impact for residents.”

Colin added, “Focusing solely on energy savings can overlook the broader benefits of WAP projects. These initiatives enhance indoor air quality, comfort, and environmental sustainability. They also stimulate economic growth through job creation and support for local economies. By creating more efficient and healthier homes, WAP projects reduce utility and healthcare costs while minimizing missed school and workdays. This comprehensive approach promotes equity by particularly benefiting low-income households and vulnerable communities. By understanding the value of non-energy impacts, it allows programs to maximize and recognize the full benefits of these programs.”

Who Should Be Involved?

During the session, Archana asked the panel to explore the key stakeholders and partners. What are the roles of government agencies, nonprofits, community organizations, contractors, homeowners, and other relevant parties in driving non-energy impacts effectively?

Amanda and Paul said, in short, everyone.

“There is no one that should be left out of the conversation around building programs that impact communities—especially the residents of the communities. Program administrators need to understand who they are serving, what the priorities of their clients are and what the challenges might be. Partnership with other organizations is also key to running effective programs and making sure limited funds are working as hard as they can. We should not have to duplicate administrative work, and neither should residents. Contractors and training providers are also vital to the success of programs. They need to understand the mission of the work and the process to get jobs done, so every step of the program runs seamlessly,” said Amanda.

Colin added, “Successfully integrating the evaluation of non-energy impacts in weatherization and home improvement projects requires the involvement of multiple stakeholders. Government agencies provide essential funding, set program guidelines, and oversee project implementation. Nonprofit organizations, often collaborating with these agencies, bring expertise in community development, housing assistance, and environmental advocacy, contributing valuable insights into health and social equity. Contractors and service providers perform the work and see the broad benefits of these programs, including improved indoor air quality and health outcomes. Engaging community members ensures that the projects meet their needs, while educational institutions can conduct research and offer training on non-energy impacts. Utilities and energy efficiency organizations provide technical expertise, funding, and incentives, facilitating comprehensive approaches that consider both energy and non-energy benefits. Lastly, healthcare professionals offer data on the health-related benefits of weatherization projects, highlighting reductions in doctor visits and healthcare costs, thus underscoring the importance of health in this evaluation process.”

“One of the challenges that we have is that nobody ‘owns’ all of it,” said Paul. “The Department of Energy isn’t about health. The Department of Health & Human Services isn’t about energy. And so forth. Instead of each stakeholder saying, ‘that’s someone else’s responsibility,’ we really need to come together and each contribute what we can. Beyond program sponsors, it also takes health care, health insurance, community organizations, and industry. Industry may look at low-income families as not able to purchase beneficial technologies, but we need to collectively move to a place where we recognize that there are delivery mechanisms for technology and support those delivery systems. It also takes education of residents so that they know what the problems are and, more importantly, how they contribute to solutions. Lastly, but in some ways most importantly, it takes the ‘middle actors.’ The contractors and other professionals who are the ones actually in people’s homes. Along with community organizations, these are the people who residents look to and trust. We need to treat the contractors as valuable and thoughtful contributors to the overall landscape, with needed experience and important contributions to how we deliver home performance. Too often contractors are seen as simple conduits between research/industry and the end user, when they have so much more key knowledge to contribute.”

What are the Potential Metrics for Qualification?

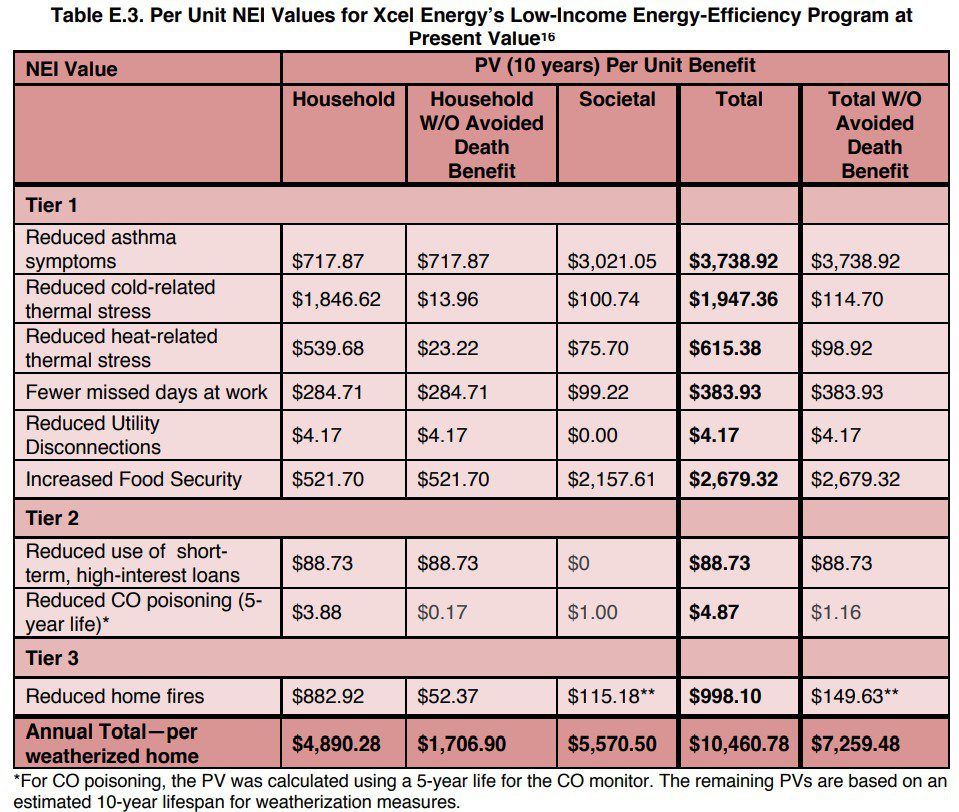

In his career, Bruce has published specifically on non-energy impacts for more than two decades. He’s found that the lifetime value of non-energy benefits are more than the energy savings. He also evaluated the DOE’s WAP from 2008 to 2010 and found that the average total benefit per unit weatherized is far more than the average total cost. In his most recent study on Southeastern states, the results suggested that energy efficiency improvements in low-income homes can have a cascading positive influence on financial issues, general health, life satisfaction, and major life events.

So, there are substantial efforts to measure the non-energy impacts because everybody likes to measure success in the form of numbers, or the dollar amount of impact.

“Comprehensive low-income weatherization programs install measures such as air sealing, insulation, and new heating and air conditioning systems to reduce energy consumption and reduce household energy bills. Research shows that installing these and other energy conservation measures can also yield important NEI,” said Bruce. “It is exceedingly important to estimate NEI in order to:

- Create comprehensive evaluations of low-income energy efficiency programs,

- Demonstrate the value of funds invested in weatherization beyond saving energy (reduce GHG emissions, create jobs, improve health),

- Identify opportunities to blend weatherization and other programs (healthy homes, climate change resilience), and

- Attract additional funding for weatherization, such as from healthcare.

The range of NEIs accruable from weatherization is quite impressive. Examples of important NEIs include creating local jobs and reducing emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases. Our NEI research focuses on important health and household benefits and how those benefits can then also benefit society. More specifically, we believe it is important to assess these types of health and household benefits measured through pre-post weatherization research designs:

- General health of occupants,

- Chronic health conditions of occupants,

- Acute health events experienced by occupants,

- Financial assistance required by households,

- Financial hardship reported by households,

- Home conditions,

- Life satisfaction of occupants, and

- Fewer days missed of work and school.”

Of course, there are challenges to measuring these impacts. “Challenges in measuring these impacts involve data collection consistency across projects and regions, comprehensive data gathering, the lack of standardized metrics, and ensuring comparability,” said Colin. “Additionally, securing funding and expertise for data collection and analysis is important. Opportunities arise from providing a holistic view of the benefits, influencing policy development, attracting diverse funding, engaging stakeholders, designing targeted interventions, and developing adaptive metrics. Selecting and implementing both qualitative and quantitative metrics, stakeholders can more effectively measure, communicate, and maximize the non-energy impacts of weatherization and home improvement projects.”

Amanda noted that, oftentimes, the metrics depend a lot on what programs and/or funders want to know. “Something I have experienced as a grant administrator is that collecting verifiable research-level data is not very feasible for a program to do itself. This is a great opportunity to work with an academic partner or consultant to develop a rigorous tool for collecting data from participants that best fits your program’s and/or funder’s goals.”

Paul then brought up the fact that one of the reasons why we focus on energy so much is because it is relatively easy to quantify. “Insulation does what insulation does,” said Paul. “However, non-energy impacts are harder to quantify because not everyone reacts to exposures the same way. Therefore, we need to move away from metrics that are at the household level and be able to consider some metrics at a community or society level. We also should recognize that financial value is only one way to quantify benefits. For the child who is in school learning and with friends instead of in the emergency department trying to breathe, what was the value of the intervention that reduced the frequency of asthma attacks? For the parent who is holding down a job and supporting his/her family instead of taking the child to the emergency room, what was the value of the intervention that reduced the frequency of asthma attacks? I don’t have all of the answers for how to quantify non-energy impacts, but we should look for more appropriate metrics such as reductions in adverse outcomes.”

Monetization

Bruce said that it’s important to monetize NEI with respect to households, society, and ratepayers. For example, it is possible to estimate the reduction in healthcare costs to society when fewer occupants are hospitalized from thermal stress after homes are weatherized. Households’ out-of-pocket medical expenses may decrease post-weatherization because they will have fewer emergency room visits for asthma and COPD problems. Households may be better able to pay their utility bills post-weatherization, which will reduce utility costs associated with notices and disconnections. “Overall, our monetization research supports the conclusion that weatherization NEIs typically exceed weatherization job costs,” said Bruce.

“We advise taking an inclusive approach to NEI assessment projects. There are a wide range of stakeholders who can both help design and implement NEI projects and who will find NEI assessments and monetization quite valuable. The stakeholders include low-income energy efficiency program administrators at the federal, state, local and utility levels, regulatory bodies, subject matter experts, disciplinary experts, weatherization recipients, multifamily building owners, and healthcare.”

We know that there are many impacts from home performance—now it’s time to quantify them to show our communities the benefits that go beyond energy savings.

Notice: This manuscript has been authored by UT-Battelle LLC under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725 with the US Department of Energy (DOE). The US government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the US government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for US government purposes. DOE will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the DOE Public Access Plan.

Acknowledgement: We are thankful to the expert panelists Dr. Paul Francisco, Amanda Jimcosky, Colin Choney, and Dr. Bruce Tonn for participating and sharing their expert opinion.