Sep 18, 2023

Blower Door Testing in 1915?

A blower door test, along with before and after load calculations of a leaky 1915 home, show the value of these technologies for remodelers and homeowners.

By: Ben Walker

A lot has been written about making new homes energy-efficient, comfortable, and healthy. That’s important, but as more communities with high-performance new homes become available, more owners of existing homes want the same benefits.

Just tightening up a home isn’t enough, however. Homeowners want you to quantify the improvements. That’s where testing earns its keep.

Weatherization contractors and remodelers who specialize in energy retrofits talk about “testing in,” or performing blower door, duct, and infrared tests on a home before work begins. This establishes a baseline to compare the finished home to, but it also offers other benefits. The results serve as a roadmap for making the home more efficient and are also a very effective sales tool.

To demonstrate how testing-in works and what it reveals, I decided to go back in time and perform a blower door test on the home I grew up in.

A Real Antique

In 1983, when I was 12 years old, my parents had recently divorced. My mom did the best she could but things were tight, so we couldn’t be too picky about housing, so she, my little brother, and I ended up moving into a 1500 sq. ft., two-story home built in 1915.

It had 2×4 framing and wood siding but no structural sheathing. The interior walls were covered with wooden planks and wallpaper. The insulation was, hard to believe, crumbled up newspaper! When the wind blew, you could feel it inside.

The heater was also an antique: an oil-burning stove in the living room with a squirrel cage fan to circulate air. It didn’t work very well. Even though winters in Washington State are fairly mild, with temperatures rarely below the mid-30s, it barely heated the first floor, and that was only if we hung blankets over the stairway to keep the heat downstairs.

A few years after we moved in, the oil stove gave up the ghost. Short on cash, my mom bought portable space heaters that could barely warm a single room and continually blew the circuit breakers. In winter, she would turn on the electric oven in the kitchen to take the chill off; when it got super cold, she would also turn on the stove burners.

This home was obviously desperate for the benefits of a weatherization program, though there wasn’t one available at that point (and my mom would have been too proud to accept that kind of help anyway).

Like A Barn Without a Door

The current 2015 Washington State Energy code sets the maximum air leakage rate for new construction at 5 air changes per hour at a test pressure of 50 Pascal—known in the industry as 5 ACH50. I was curious about how this home would score, as little had been done to improve the thermal boundary.

Before testing an old home, it’s important to note any relevant environmental factors. For instance, it’s common to use the blower door to depressurize the home for the test, but in this case, there were contaminants in the attic and rodents in the basement, so depressurization would have pulled those contaminants into the living space. Instead, we put the home under positive pressure and measured air exfiltration.

In most cases, we go around the house with a smoke pencil to look for individual leaks, but there were so many in this house that it would have been pointless. For instance, the test protocol requires that all exterior doors and windows be closed, but the leakage was so bad that I double-checked that all the windows were closed. They were.

It was like a barn without the front door attached.

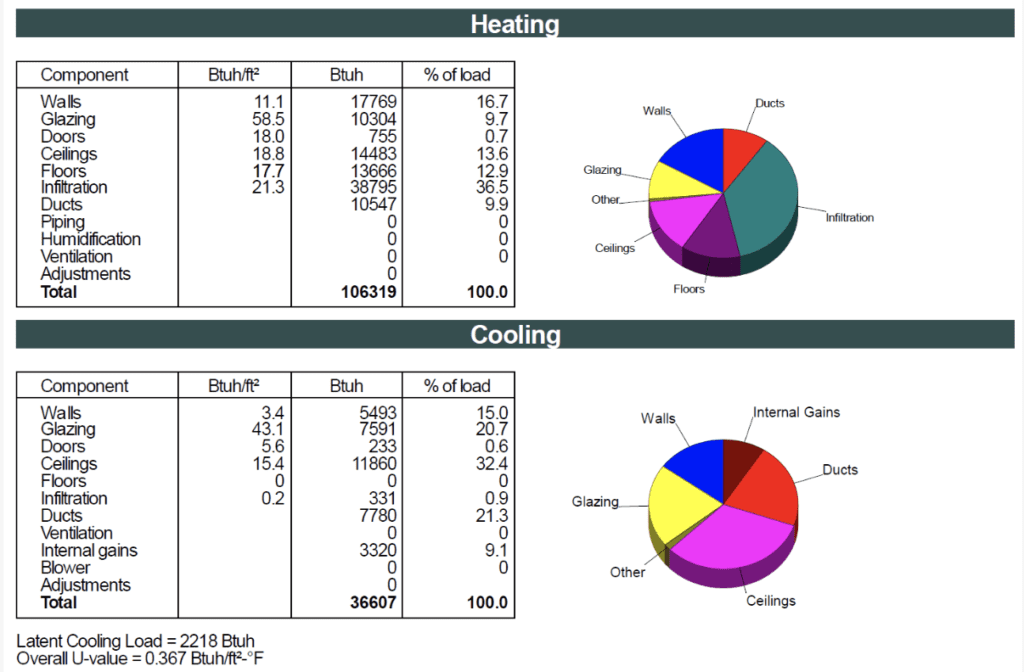

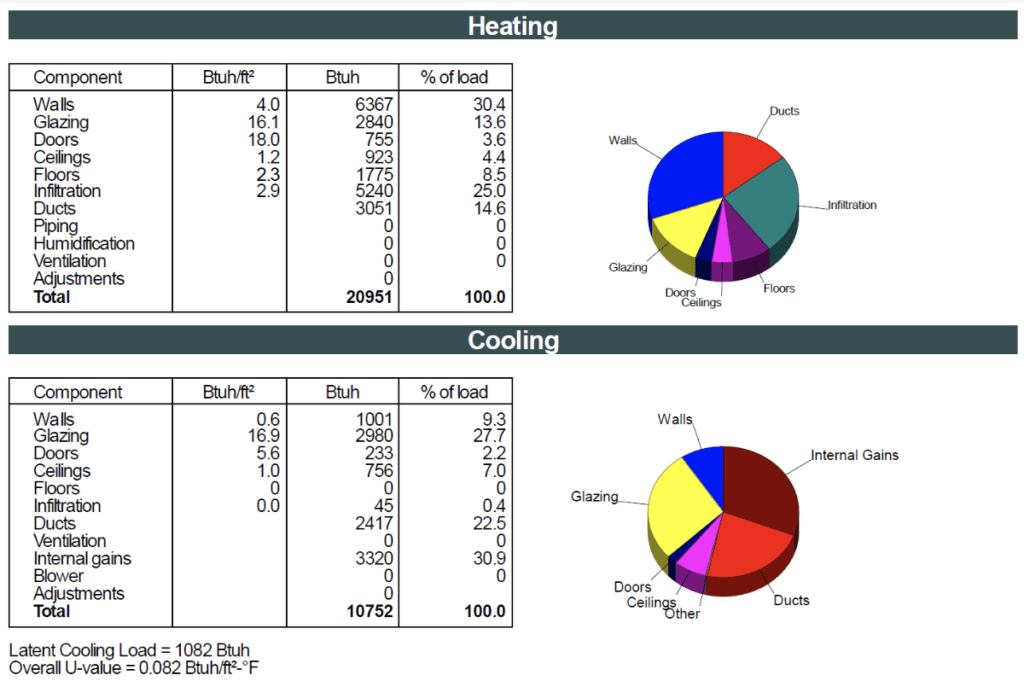

As part of the test-in procedure, we also performed a heat load calculation using Wrightsoft. The load calc tells us how much heating and cooling the home would need in its current state. We also calculate what the optimal size of the heating and cooling system would be after improvements.

Wrightsoft asks you to input parameters like square footage and orientation. In the past, this required someone to physically measure the structure, but now we get a lot of that information from Zillow and Google Earth. It also asks for an air leakage rate. A lot of contractors take a guess, but having a number from an actual blower door test makes the results much more accurate.

The Envelope Please

Any guesses on how my childhood home scored?

The answer is that we calculated a leakage rate of 22.53 ACH50 or 4.5 times the code minimum for new homes. My memories of discomfort weren’t imaginary. We had been heating the outdoors.

The load calculation report consists of four pages with lots of numbers that your average homeowner won’t understand, but you can get the gist of what they mean from the pie chart.

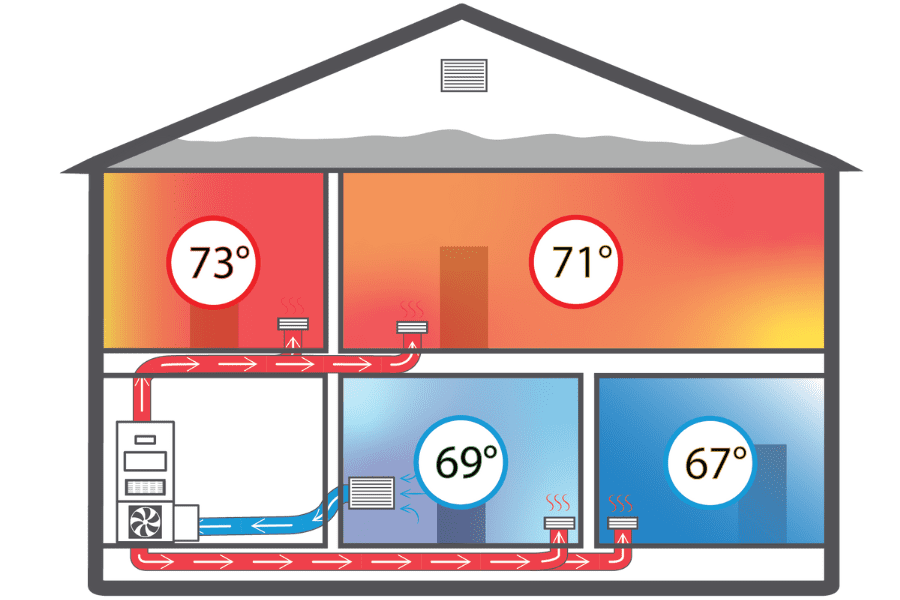

The test-in showed a load of 106,319 BTUs per hour, which would have required an 8.5-ton commercial heating system to keep it comfortable. Adding insulation and lowering infiltration to 5ACH50 would bring the load down to around 10,752, which would only require a 2-ton unit.

Of course, that begs the question of how to go about making the improvements. Since this house has no sheathing or insulation, the best approach would be to add both. That would mean removing the siding, insulating the stud bays, and adding sheathing and new siding. The sheathing would be enough of an air barrier to reduce air leakage to code.

Tightening up the home would also offer non-energy benefits, such as more thermal comfort with even temperatures throughout. The home would also be more healthy, with fewer mold and moisture problems.

Profit and Non-Profit

It takes about an hour and a half to set up the blower door, run the test, and explain the results to the homeowners. With Retrotec’s rCloud software and the mobile version of Wrightsoft, you need only add a portable printer, and you have a detailed printed report you can leave behind.

Although some contractors charge for this as a standalone diagnostic service, my staff has also spoken with quite a few insulators, HVAC contractors, and remodelers who use the test results as a sales tool. The ones we’ve spoken with say that having a report that quantifies the home’s problems as well as the benefits of efficiency improvements definitely improves their closing rate.

Think of it like getting lab work. If you’re chronically tired and achy and the doctor points to a number that shows Lyme in your bloodstream you’re going to take those antibiotics, no matter how much you dislike pills.

The problem is that just as many people can’t afford health care, many also can’t afford to improve their home’s performance. For instance, my mom still owns this home and currently rents it, but she has not taken significant steps toward improving the thermal envelope. The reason is the same as it was in 1983: money.

In fact, all the homes in this neighborhood are similar, and all are occupied by low-income families, most of whom are stuck with energy bills that are way too high but lack the resources to do anything about it. It’s a story repeated across many old neighborhoods in this country, which is why I’m a big advocate of weatherization assistance programs.

Resources

- Washington State Climate Data

- Washington State Weatherization Program Info

- http://www.energy.wsu.edu/BuildingEfficiency/EnergyCode.aspx

- Full Home Report As-Is

- Full Home Report After Rehab

Additional Resources

This article was originally published in the Retrotec Blog and is republished with permission.