Sep 13, 2024

Building Forward in the Face of Fires

How Passive House building methodologies can improve fire resilience for individual homes and communities, even compared to standard best fire-aware practices.

By: Andrew Michler

While Passive House buildings are rightly touted for their comfort, health, and energy savings, they bring another benefit that is often overlooked but can be critical in the western United States and other arid climates—their inherent survivability in wildfire events. Nearly 40% of all homes in the U.S. are built in what is called the wildland urban interface (WUI), and nearly all of those homes located west of the Mississippi are vulnerable to wildland fire. This risk affects not just individual homes; as development expands and climate impacts make for a more brittle ecosystem, neighborhoods and entire communities are directly threatened by wildfire. Additionally, anyone who is living in the West either already has or is likely to experience severe air pollution from wildfire events that can last days to months at a time.

My personal experience with wildfire goes back to losing our family home in the 1991 Oakland Hills fire that consumed nearly 3,500 homes in a matter of days. Helping my father rebuild was what kickstarted my career in building and design. When I launched the design process for a Passive House in the Colorado Rockies in 2013, wildfire survivability was one of my guiding principles and the key element in choosing my building materials. In the years since, I have increasingly come to appreciate how significant an improvement a Passive House is in terms of fire resilience, even compared to standard best fire-aware practices.

Fire is never far from my mind these days. In the summer of 2020 the Cameron Peak fire, the largest in Colorado’s history, burned up to the border of our property. Then, on December 30th, 2021 the Marshall Fire in Boulder County, Colorado consumed more than 1,000 homes. With a massive movement to rebuild, there has been a significant emphasis—including some reasonable subsidies—to build beyond code in terms of both energy usage and fire resilience. But, there has also been a competing movement against building back better. Many large-scale builders are offering homes built just to meet code, with minimal or no consideration of occupant well-being or fire survivability beyond what is required. This is a typical market response; there are many vulnerable survivors who are experiencing significant financial and time stresses to build back to what they had. Many of these builders also successfully lobbied to repeal a new 2021 building code that would have reduced energy consumption of the rebuilt homes.

To provide a path toward building, not just back, but forward, I teamed up with Rob Harrison, an architect, and Joubert Boutique Buildings, a custom home builder, and we developed a low-cost, move-in-ready home, which is certifiable to PHI standards, to help families who do not have the budget or time to pursue a custom home. We are working in partnership with local and state government bodies, media like Rocky Mountain PBS, and Xcel Energy, to promote and make available the advantages of Passive House, while keeping a clear eye on the environmental stress and vulnerability of our communities.

Because of the core thermal dynamic physics built into every Passive House, its response to very extreme events such as a fire front has valuable lessons as communities rebuild. Before I get into the details of our RESTORE Passive House, I want to review some of those lessons.

Passive House Advantages

The first relevant principle is a Passive House’s simplified form factor, which is generally utilized to reduce thermal losses from exposed surface areas. During a fire, the first exposure to a structure is from firebrands—flaming or glowing fuel particles—that can surround the building and easily ignite debris or the cladding of the structure itself. This risk can be intensified with a heat front-driven wind that creates air eddies around the building’s protrusions, further lodging firebrands in vulnerable areas. Passive House envelope details typically reduce or eliminate complex exterior geometries, allowing firebrands to blow past the structure rather than lodge in corners, crevices, complex roof valleys, and so on.

An approaching fire front will be presaged by a wall of superheated air and thermal radiation. Contrary to popular belief, this will not in itself usually ignite flammable materials, but the thermal stress can easily break windows. In cases when the superheated air sticks around long enough, homes have been compromised by a single or double pane of glass becoming the critical failure point for the entry of firebrands. Even homes made from concrete have often succumbed to wildfire because of compromised fenestration.

The use of triple panes and substantial window frames, which are common in Passive Houses, will significantly reduce this point of risk to the envelope, as it takes time for each pane of glass to fail from heat stress. By upgrading to tempered glass, the resilience of the assembly would be further improved, and the overinsulation of the frame, another typical Passive House detail, will also reinforce the window’s integrity.

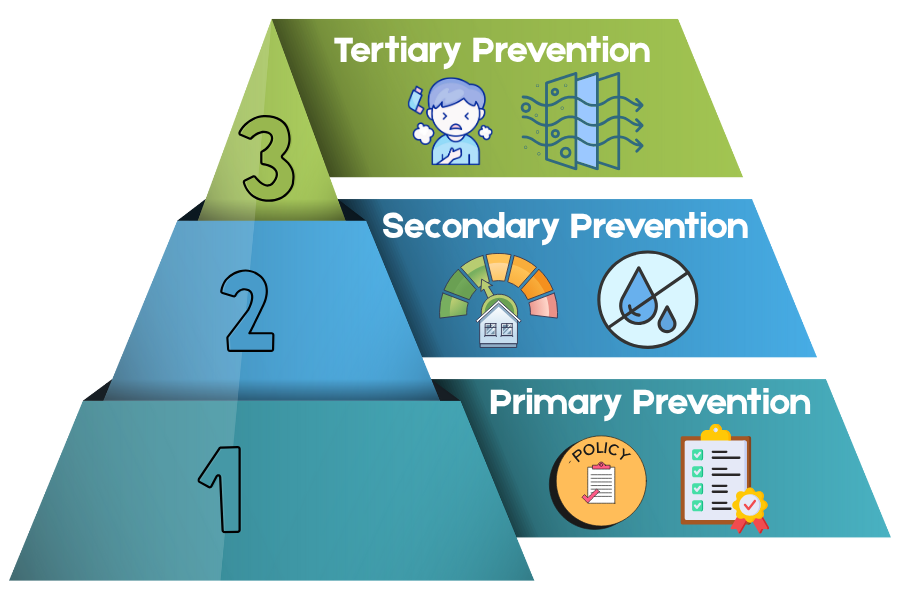

The choice of fire-resilient claddings, decks, and fences, type A roofing, and less flammable vegetation nearby are standard firewise practices. But, even with the best of strategies, a significant fire event can overwhelm a building. If fire does compromise the envelope, then the materials used in the walls and roof can have an impact. Many Passive House practitioners, including myself, have eliminated foam insulations from our assemblies, due to environmental and health concerns. Although fire retardants—about which there are many environmental concerns—are routinely added to foam insulation products, these are still likely to encourage flame spread more than such environmentally benign materials as dense-pack cellulose or mineral wool, or even straw panels. These insulations have both low- or zero-flame spread and also deplete the source of oxygen from sheathing and framing compared to lighter insulation materials like fiberglass.

By fully insulating assemblies, including the service cavities, their R-values are further improved, and the possibility for flames to spread in the structure is reduced. This strategy is particularly valuable in a roof where appropriate insulation up to the roof decking, eliminating vents and covering all framing, provides little access for fire ingress. A continuous exterior insulation like mineral wood board or a fire-rated wood fiber board improves the fire resilience of the cladding and roof, while adding a rainscreen and creating a vapor-open assembly.

All these Passive House design elements in concert closely parallel best practices for fire-resilient design. While there is no way to guarantee that a building will survive a fire event, the odds are dramatically reduced that a single point of ingress will lead to catastrophic failure. In events like the Marshall Fire and Oakland Hills fire, often it is one house going up in flames that leads to another, resulting in a domino effect that swallows entire communities. So, fire-resilient Passive House development at scale is one of the most effective approaches to help alleviate community vulnerability and improve survival rates.

While wildfire events are devastating to those immediately affected, many more people are affected by smoke exposure and its potential damage. In the article “Keeping the Smoke Out” authors Cameron Munro and Joel Seagren show how a Passive House in Canberra, Australia had performed in a significant brush fire smoke event in January 2020, considered the capital’s worst air quality on record (See Renew, April, 20, 2020). With standard heat recovery ventilation turned on, the home had, at worst, half the particulates compared to outside over a five-day time period. An identical passive house nearby incorporated a HEPA prefilter, which resulted in a multiple-times decrease in indoor pollutants, only occasionally spiking a little above recommended heath levels. A code-built home was measured to be only slightly better than outdoor air quality.

During the Marshall Fire, builder Mark Attard’s personal house, a Passive House retrofit, was at the very edge of the fire front. When he came back, he found virtually no smoke damage, while all of the neighbors’ homes that did survive were considered unhabitable pending smoke rehabilitation.

Restoring Communities

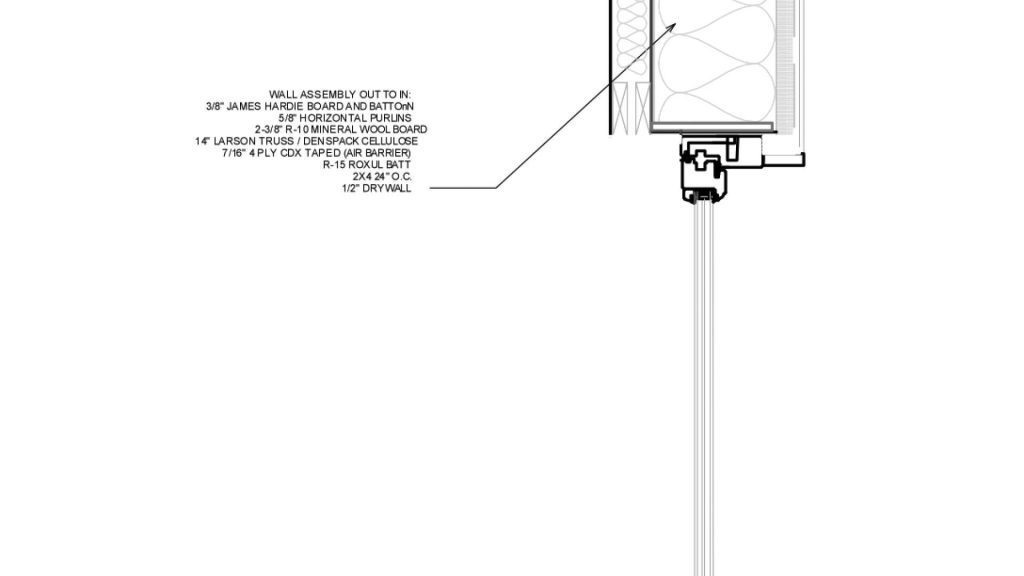

Designed for the Sagamore neighborhood in Superior, Colorado that lost nearly 200 homes, the RESTORE Passive House incorporates all of Passive House design advantage. It starts with a simple L-shaped form factor. It can be rotated or flipped to provide southern solar access even with adjacent houses. Both the roof and cladding are metal, and the assemblies include a layer of mineral wool board backing the sheathed 2×8 framing to provide a cost-effective and simple-to-construct wall. The mineral wool also is used to overinsulate the triple-pane windows and double as the rain screen. A fully insulated cathedral second-floor ceiling and the elimination of roof eves and vents help complete the fire-resilient envelope system. The walls and roof use dense-pack cellulose insulation with the sheathing acting as the air barrier.

I took inspiration for this assembly from my own Passive House, which has a vapor-open assembly using mineral wool board over cellulose-packed Larson trusses as the primary insulation system. This is but one of many fire-resilient and high-performance options, so any potential homeowner should be careful to evaluate the best combination that fits the budget, material availability, embodied carbon, and climate appropriateness.

The RESTORE Passive House will use a PHI-certified Brink 325 HRV, which has an impressive 91% efficiency installed. Each floor will have a hallway mounted 6-kBtu mini split, each with its own condenser to maximize efficiency when used for zone heating and cooling. We are debating the merits of jumper ducts to help balance the heat distribution of the bedrooms to ensure comfort but keep mechanical costs down. A heat pump water heater and an all-electric kitchen will ensure the clients are eligible for a $10,000 all-electric home state rebate. If overheating appears likely to occur on specific sites, we can incorporate custom exterior operable sliding shades on the upper levels for client control of heat gains.

As significant fire events continue to decimate communities in North America and all over the world, Passive House should be considered a primary design tool to help harden our homes and communities to work within the new reality of fire-shaped landscapes.

For more information on the RESTORE Passive House, visit www.passivhaus.city. To watch the PBS show about rebuilding after a fire, see https://www.rmpbs.org/colorado-voices/passive-houses.

This article originally appeared in Passive House Accelerator and is reprinted with permission.