Nov 15, 2022

Are Consumer Protections in the Heating and Cooling Industry Working?

Charles Cormany shares information on getting the right HVAC system and installation.

By: Charles Cormany

Along with plumbing and electricity, Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) is one of the three major systems in a home or building. Getting an HVAC installation right is the difference between having a comfortable, efficient system that saves energy versus an oversized, wasteful setup that will cost the customer money for years.

HVAC systems all have an expected useful life (EUL) — a fancy way of saying things wear out and will need to be replaced. According to industry standards, the expected useful life for a residential furnace is 18 years. In practice, many systems continue to function beyond their expected useful life. This means that the performance of a new furnace you put in now will likely affect energy bills and comfort for a long time. Consumers and contractors often overlook this point when replacing or upgrading HVAC systems.

Most residential HVAC systems are replaced upon failure. The immediate need is to restore service quickly and frequently at the lowest possible price. Few contractors are concerned about providing the best solutions for your long-term needs. In fairness, most respond to customers’ requests and often pick the quickest and easiest solution. This short-term thinking has a cost, though.

At Efficiency First, we have always supported high-performance solutions. This doesn’t necessarily mean choosing the highest-end equipment. You can have the most expensive equipment on the planet, and if it is not installed correctly, you will have performance issues. On the other hand, you can use less sophisticated equipment that is well-designed and installed correctly and achieve incredible results.

The Need for Data

Most heating and cooling contractors learned their trade from others. The things they do today are based on what they were taught to do by their mentors. But a lot of what contractors think they know is wrong.

About forty years ago, someone was curious about the actual operational costs related to heating and cooling. Was it more effective to use natural gas or electricity? What role does insulation play in the equation? How vital are windows to comfort? How can we determine the best solution for a specific building without utility bill data? Questions like these are hard to answer without data. Engineers created special devices to accurately measure things like building pressure (blower door), duct leakage (duct testers), insulation levels (Infrared cameras), and methods for identifying window coatings. As a result, an entire new industry was created based on building science.

For many, the results were surprising. Many standard practices handed down from generation to generation were not necessarily effective and, worse, unnecessary. An easy example is equipment sizing.

Even after all this time though, many HVAC installers still rely on rule-of-thumb sizing for HVAC systems.

The Impact of Rule-of-Thumb Calculations

Here is an example that shows why rule-of-thumb sizing is a problem.

In California, rule-of-thumb residential HVAC sizing is based on 500 square feet per ton of cooling. So a 1,500-square-foot house needs 3 tons of cooling. Easy, right?

The problem is that this ignores a number of important questions.

- How many stories does the building have?

- Is there a basement crawlspace? Is the house constructed as a slab on grade?

- Is the attic insulated? To what depth? What about the walls and under the floor?

- Are the windows single or double-glazed? Do they have low-E coatings?

- What climate zone is the building in? (The weather in Tahoe is not the same as San Francisco).

- The list goes on…

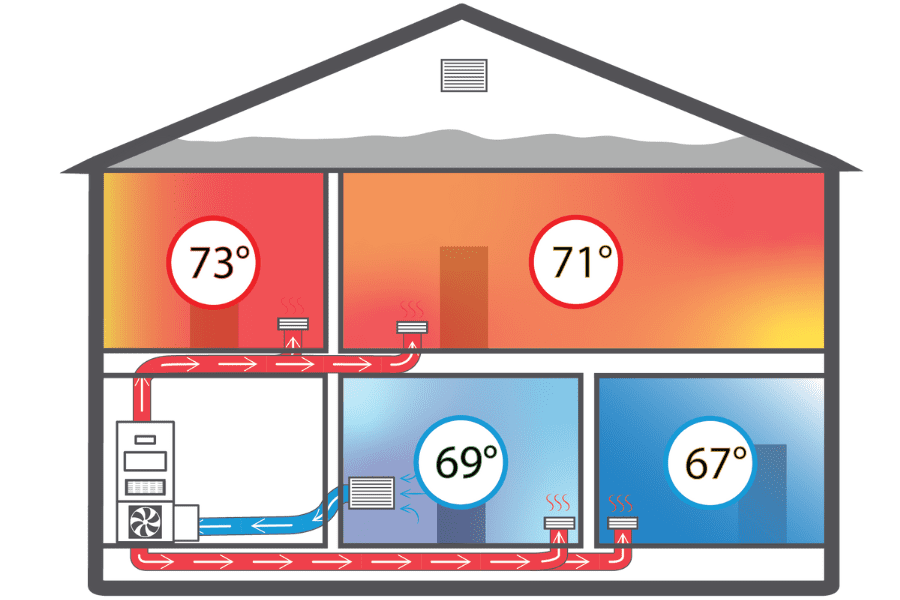

As a result of rule-of-thumb sizing, most California residential HVAC systems are oversized, and not just a little bit. Most designs are at least twice as big as needed and sometimes much more. Ducts need to be appropriately sized too. Chances are the ducts were sized by the rule of thumb too, which tends to undersize ducts. Not to mention that the average duct system in California leaks over 35 percent of the conditioned air outside the building.

Oversized heating and cooling systems with undersized ducts are inefficient, do not deliver true comfort, are noisy, and are expensive to operate. If proper sizing is such a problem, why hasn’t anything been done about it? The simple answer is that for years, the energy to power HVAC systems was cheap, operational costs were minimal, and environmental impacts were not considered. Comfort and noise were not addressed. The public just accepted the results.

Regulations Address the Issue…But Regulations Require Enforcement

Legislation and updated building codes supposedly address these issues. The state requires a heating load calculation and independent testing by a third party before a building department can sign off on a project. HVAC third-party testing, referred to as HERS compliance testing, must be performed by a state-licensed Home Energy Rating System rater (HERS). The rater verifies refrigerant charge and duct leakage and confirms the system works to the design specifications.

The solution looks great on paper and works well when it is enforced. Unfortunately, for many building officials this is just more paperwork, and they are happy to look the other way, which is a massive loss for the industry, consumers, and the environment.

Another problem is that the contractor is responsible for hiring the “independent” third-party rater. Think about that for a minute. The contractor pays the quality control inspector. What happens if the jobs don’t pass? Failing jobs is part of a HERS rater’s responsibility. The problem is if you are an honest HERS rater and fail projects, the contractor has the option to hire another rater. We have seen this happen. It’s amazing how, suddenly, with a new HERS rater, a previously failing projects passes with no other changes.

And that’s assuming that a contractor even pulls a permit. An even easier solution for the contractor is to tell the customer that their permit is optional, or worse, convince them that if they pull a permit, their property will be re-assessed and their taxes will go up. This happens all the time and is a real issue.

Studies show that 85 percent of projects included a building permit before mandatory HERS testing. When third-party verification was required, the rates plummeted. Today less than 10 percent of residential HVAC changeouts have a permit. The easy answer for contractors is to avoid the permit process to continue business as usual.

The California Energy Commission is aware of the issues with the lack of permits and misaligned incentives for the HERS process. Unfortunately, the answer is not simple or cheap. There have been proposals, such as tracking serial numbers as the equipment is sold, to ensure it is installed with a permit. Equipment distributors are not fond of this approach.

The sad thing is that the losers are the consumer and the environment.

High-Quality Work Costs More

There are HVAC contractors who abide by regulations and do great work. They perform load calculations, size their ducts appropriately, and are most likely installing heat pumps instead of fossil fuel-burning furnaces. As you might imagine, playing by the rules cost more. Pulling a permit takes time. The permit itself costs money, as does paying the HERS rater for the compliance testing. Obtaining a permit can easily add $750 to $1,000 to the price of a project. Competing bids from contractors who avoided permits was a huge frustration to me when I was a home performance contractor. The bids were not apples to apples. Thankfully, our sophisticated client base understood the difference and our value. That is not typical.

Aligning Incentives

One solution is to make sure contractors have some skin in the game, with incentives based on actual energy bill savings. This is happening now in parts of California, where utilities are rolling out new rebate programs, known as FLEXmarket or Market Access. The rebates are paid based on the amount of energy the project saves after it is installed, instead of on modeled predictions. If a project reduces the utility bill, the rebate is paid. Save more energy than anticipated? The rebate increases.

I bet contractors’ sales messaging and installation procedures will be different if they know they’ll get paid more when their projects deliver actual, measured results.

Consumer Awareness is the Key

Until consumers start demanding better quality and full compliance from contractors, I have little confidence things will change. Triple bid proposals and choosing the lowest-cost option is a real trap. Contractors and the industry need to make people aware of the long-term impacts of poor-quality HVAC installations.

Consumers also need to know about regulations and the consumer protection they provide. Contractors need to include long-term operational costs as part of their messaging. Regulations can help – for example, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) is phasing out natural gas appliances, which will not be allowed in the state after 2030. The industry needs to promote the adoption of electric heat pumps over fossil fuel alternatives, such as gas furnaces.

Until consumers understand the difference, the scales are tipped in favor of low-cost, minimal effort, maximum profit HVAC replacements. We need to prop up high-quality contractors and help them succeed. A lot is riding on the outcome.

This article originally appeared on the EFCA blog and is reprinted with permission.