Jun 5, 2023

Is the Inflation Reduction Act a Catalyst for Puerto Rico’s Microgrids?

The extremely expensive electricity and the precarious condition of the power grid in Puerto Rico have served as the perfect motivators for increased solar-plus-storage microgrids. But, for the vast majority, a solar microgrid is still a distant desire.

By: Maximiliano Lainfiesta and Michael Liebman

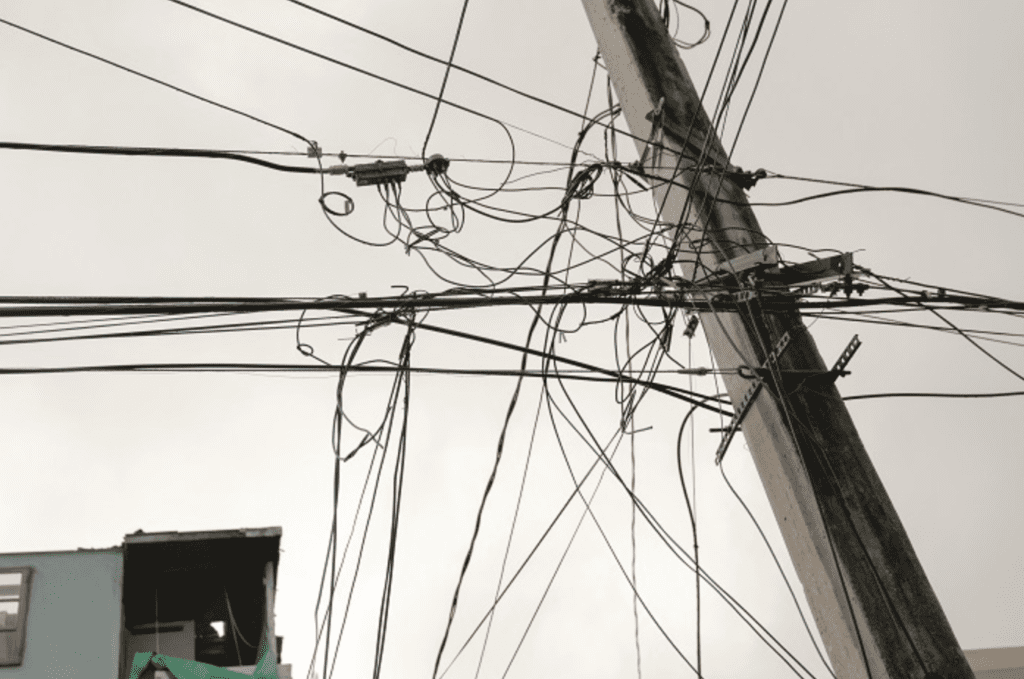

It is not often that you hear about power grids or utilities in music videos, despite their key roles in our daily lives. But this happened last fall, when multi-platinum musician Bad Bunny released the video “El Apagón” a couple days before an island-wide blackout during Hurricane Fiona. The video described the electricity challenges that Puerto Ricans face in normal times and disasters including hurricanes and earthquakes.1

Puerto Rico has the lowest gross domestic product per capita and the highest poverty rate in the United States.2 The average Puerto Rican pays more than double the price for electricity compared to people living in the mainland United States.3 This means that Puerto Ricans have the highest energy burden (percentage of income spent on energy) in the nation.

The service is not only expensive – it is also unreliable. Daily power outages happen all over the island, affecting everyone. Outages impact the most vulnerable sectors of the population more severely, including those who cannot afford to have emergency backup systems.4

The extremely expensive electricity and the precarious condition of the power grid have served as the perfect motivators for increased solar-plus-storage microgrids. As it stands, Puerto Rican individuals and organizations see the appeal of solar microgrids. For some fortunate ones, these onsite solar-plus-battery installations have helped drop electric bills to near zero and have provided reliable power during daily outages and during extreme and extended outages caused by hurricanes and rain.5

But, for the vast majority, a solar microgrid is still a distant desire.

Fortunately, the Inflation Reduction Act holds the potential to ensure that clean power is more affordable and obtainable for more communities. The IRA has two main objectives: first, to lower energy and health care costs, and second, to help bring down the deficit. The law focuses strongly on renewable energy and includes new mechanisms to help underserved Puerto Rican communities pay for green energy upgrades such as efficient appliances and rooftop solar panels.

Until now, Puerto Rican nonprofits and local governments could not directly take advantage of the solar Investment Tax Credit because they are not required to pay federal taxes.6

In Puerto Rico, nonprofits like homeless shelters and pre-vocational training centers provided vital support to community members after Hurricanes Fiona and Maria, including offering food, water and supplies and assisting with communication. Current microgrid market prices make it impossible for most of these organizations to make the shift to renewable energy, especially in disadvantaged communities, cutting lifelines during times of crisis.7

The IRA expands the reach of energy incentives to new beneficiaries in various ways, including a direct-pay option for the ITC. This means that instead of only helping large firms lower their tax bills, organizations that pay no taxes can receive the ITC as a direct payment.8

The new direct-pay option offers different percentages of the overall project cost, with the amount based on the project meeting certain criteria, such as offering additional incentives for lower- and middle-income communities. With the magnitude of the incentive up to 40% plus financial and technical assistance, the IRA could unlock access to and ownership of clean power for nonprofits and governments, providing crucial support to disadvantaged communities.9

As the IRA is rolled out in Puerto Rico, an emphasis on implementation will be crucial to ensure that history does not repeat itself. In 2017 after Hurricane Maria, the Federal Emergency Management Agency allocated billions of dollars toward reconstructing the electrical grid. Over five years later, most of these funds still have not been spent. These funds should be distributed urgently and strategically to ensure the grid is resilient into the future.10

For the IRA to truly help transform Puerto Rico’s energy future, the stakeholders throughout the territory need to come together and focus on three key support areas:

1. Financial institutions must step in to drive equitable adoption, including serving as a bridge between project kickoff and reimbursement.

Without financial structures in place designed to meet communities where they are, lower-and-middle-income-community-critical facilities will struggle to participate in the program. For example, let’s say that a shelter for victims of domestic violence located in a lower-and-middle-income neighborhood wants to use the direct-pay option toward a system that will include solar and battery storage (sized for critical load) and is estimated to cost $100,000. If the contractor meets all the requirements for the direct-pay option, the facility should be entitled to a $40,000 direct reimbursement after filing: 30% of the project cost for the ITC and an additional 10% for being in a lower-and-middle-income community.

However, for many facilities, having to pay this $40,000 upfront could be a prohibitive barrier. There are two different paths that could overcome this challenge for facilities with less cash on hand. The first option involves the facility paying the 20% down payment that most financial institutions require and then having the remainder of the project financed with a structure designed specifically for this program. This would include that the 40% coming from the ITC direct payment must be paid sooner than the remaining 40%.

Another option that would work especially well with smaller systems could involve the shelter paying for 60% of the project and then getting a low-interest bridge loan for the 40% to cover the period between kickoff and reimbursement. Financial institutions must step in to offer these options and create others to ensure that this program is not out of reach for low- and middle-income communities.

2. Training for project customers and for engineering, procurement, and construction contractors is crucial.

Based on the rapidly rising electricity prices and many outages, contractors throughout Puerto Rico have been inundated with demand, which is particularly problematic as Puerto Rico’s struggling economy has made finding qualified staff challenging. Tracking the requirements for this program, along with other key programs, including the Community Development Block Grants, can be difficult.

The program administrators must create easily digestible content and provide trainings to contractors to ensure that they fully understand the opportunity and requirements of this program. Similar training and materials should also be available for customers.

As companies pop up in Puerto Rico to take advantage of the huge amount of demand, customers must know how to vet contractors. For example, for projects to receive the 30% direct payment, contractors must comply with various rules, including paying a “prevailing wage” and having apprentices complete a set portion of each project’s labor hours. This portion starts at 12.5% in 2023.

3. Pairing the direct pay with other available programs could be transformational.

In Puerto Rico, there is an incredible amount of funding available for other programs that has not been deployed. Over $12 billion was allocated for grid reconstruction after Hurricane Maria, and in late 2022, the Biden administration requested $3 billion11 of additional support for solar deployment in Puerto Rico.12 To drive rapid adoption of the IRA, different programs could be used together, dramatically reducing the amount that nonprofits or governments would have to pay.

The opportunities from the IRA are significant, but as leaders plan to roll out the program, they must not simply throw money at the problem. It is crucial to create a comprehensive plan that addresses the needs of lower- and middle-income areas in particular. Those communities are the least equipped to deal with electricity challenges and are eager for lasting solutions that provide resilient, affordable, and clean electricity.

- https://tinyurl.com/37arycdj

- https://tinyurl.com/493hvvxf

- https://tinyurl.com/7x5bwsw4

- https://tinyurl.com/68y664mh

- https://tinyurl.com/f69wd4jz

- https://tinyurl.com/mr428wzv

- https://tinyurl.com/2p98urf3

- https://tinyurl.com/ffdr93nf

- https://tinyurl.com/4ym8d77p

- https://tinyurl.com/mvuc9urx

- https://tinyurl.com/29x44hpp

- https://tinyurl.com/2xfetzpb

This article originally appeared in Solar Today magazine and is republished with permission.