Nov 8, 2022

Residential Electrification Isn’t Always Easy, But Implementation Barriers Can Be Overcome

Charlotte Cohn shares why residential buildings should be all-electric and how to overcome barriers to make it so.

By: Charlotte Cohn

Switching homes from fossil fuel-burning equipment to efficient electric alternatives will be a critical step toward mitigating the climate crisis. Electric heat pumps, induction stoves, and other appliances have additional benefits as well, including reducing energy costs, providing air-conditioning to homes that don’t already have it, and improving indoor air quality. However, there are significant barriers to making the switch in existing buildings. A new report from ACEEE identifies these challenges and explains how policymakers and electrification program managers can create an environment where electrification retrofits are straightforward and affordable.

Efficient electric appliances are growing in popularity across the country. Last month, California regulators voted unanimously to prohibit the sale of natural gas heating equipment beginning in 2030, a trend that may extend to other jurisdictions. Residential energy use accounts for roughly 20% of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, making building electrification a key priority for fighting climate change. If U.S. residential buildings were a country, it would be the sixth-highest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world. The time for comprehensive solutions is now.

From a technical perspective, there is no building that cannot go all-electric. But electrification upgrades are often complex and expensive projects, sometimes requiring electrical panel and wiring upgrades. Some utilities, cities, and states have already started incentive programs to reduce the up-front costs of residential electrification. Additionally, the Inflation Reduction Act includes historic rebates and tax credits that make transitioning to efficient electric homes more affordable than ever before.

What Does an All-Electric Home Look Like?

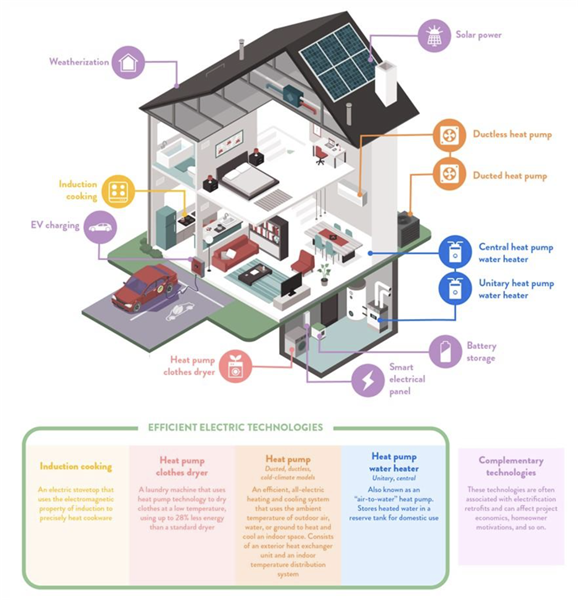

Of all the appliances and systems inside a home, there are three end uses that are the most likely to burn fossil fuels: space heating, water heating and cooking.

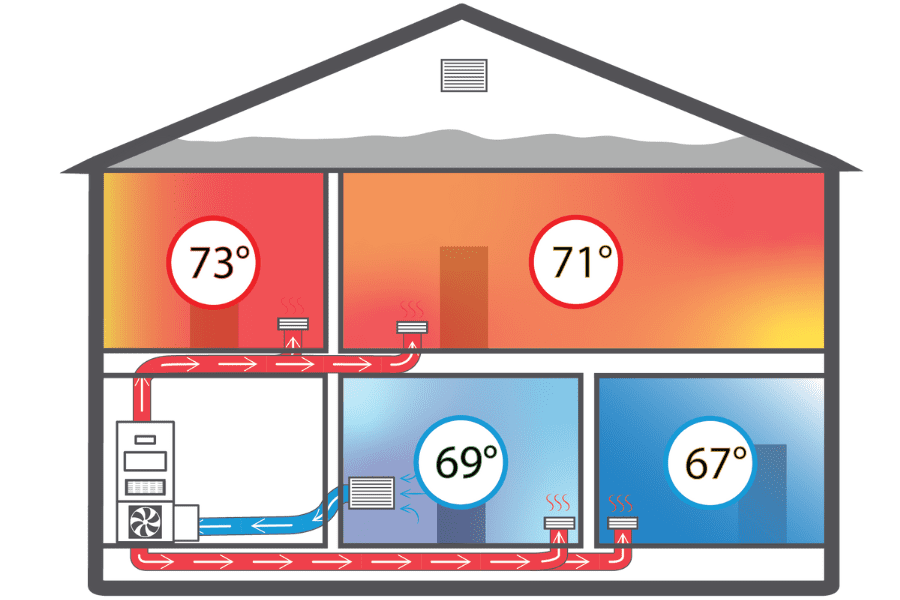

Space Heating: Heat pumps are the most efficient way to heat and cool a home. Although heat pumps have been around for decades, recent advancements have made them more efficient than ever, especially in cold climates. By exchanging heat between a home and the environment outside, heat pumps keep indoor spaces warm in the winter and provide air-conditioning during the summer. Devices that burn fuel inside homes are less efficient and emit airborne particles that can lead to asthma, carbon monoxide poisoning, cancer, and other health risks. Replacing these with an electric heat pump can lead to better indoor air quality and improved health outcomes, particularly for children, the elderly, and people with respiratory conditions.

Heat pump systems come in ducted and ductless varieties. The simplest upgrade is inside a home or building that has existing ducts in good condition. A central furnace can be swapped out for a heat pump that delivers both heating and air-conditioning. A ductless system is an option for homes that don’t have ducts. Ductless systems have wall- or ceiling-mounted units that provide climate control for a particular room or zone inside the building. In either case, proper insulation and air-sealing will improve efficiency and reduce operating costs and peak electric demand for a heat pump system. In very cold regions, a fuel backup system can be useful for when temperatures get below about 5°F.

Water Heating: Heat pump water heaters function in a similar way, heating water instead of air, and use a fraction of the energy of a conventional water heater or boiler. They store the heated water in a tank for later use. Heat pump water heaters usually are installed in a mechanical room or closet with proper ventilation to effectively pull heat from the air. New 120-volt models are more flexible and do not require a custom plug like the standard 240-volt models, allowing them to be located in more diverse locations.

Cooking and Clothes Drying: Household appliances for these uses are frequently powered by fossil fuels (usually natural gas). Efficient electric alternatives exist in the form of induction stovetops and heat pump clothes dryers. While both technologies offer efficiency and safety advantages compared to electric resistance or gas-fired versions, they frequently come at a higher price and may be more difficult to find in stores.

Weatherization, rooftop solar, battery storage, and electric vehicles offer additional benefits to an all-electric home, like lower energy costs, the ability to take advantage of special time-based electricity rates, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

Overcoming Barriers to Building Electrification

Building electrification can have a high up-front cost. Electrification program administrators can make use of rebates, tax credits, and innovative financing strategies to lower costs for home electrification. The Inflation Reduction Act offers unprecedented incentives for efficient electrification technologies, especially for low- and moderate-income households. Electrification program administrators should design their programs to ensure that building owners can harness these incentives, which include:

Rebates: Depending on income, the Inflation Reduction Act offers up to $14,000 in direct rebates for electrification. Many utilities also offer rebates for efficient electric equipment, which can be used with the federal rebates to reduce costs even more.

Tax Credits: For people whose incomes are above the eligibility requirements for the rebates, the Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits of $2,000 for installing heat pumps and heat pump water heaters.

Financing: High up-front costs can be broken into smaller payments over time. Some utilities offer inclusive investments such as on-bill financing. Third-party entities like green banks may also offer low-cost financing options for building upgrades.

Homeowners and landlords will leverage the financial incentives available only if they understand the benefits of efficient electric technologies. Our research found that because many people are not familiar with these technologies, successful electrification programs need to include consumer awareness campaigns, which often include outreach through social media, mailers, and online advertising. Programs can use billing, permitting, and census data to determine which buildings and households could benefit most from electrification.

Contractors also must understand efficient electric systems, but many are not trained to install equipment like heat pumps. Electrification programs have found success engaging existing contractors and providing training for new workers. To ensure contractors have enough business and can provide family-sustaining wages and benefits to their employees, building customer demand for electric equipment through awareness campaigns is key.

Meeting climate targets requires widespread building electrification, but many homeowners, landlords, and contractors are not equipped to overcome the barriers to electrification on their own. No single program design approach will work everywhere, but our report identifies effective strategies for successful residential electrification programs.

This article was originally published on the ACEEE website and is reprinted with permission.